Immunotherapy success could be predicted with new biomarkers

The deletion of two cancer genes, CHD1 and MAP3K7, improves how well tumours respond to cancer immunotherapy and could be used as biomarkers to help predict which patients are most likely to benefit from treatment, new research shows.

Researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, Open Targets, Netherlands Cancer Institute and their collaborators used a powerful gene-editing tool called CRISPR in a novel approach that cultured tumour cells together with immune cells from the same individual to measure immune killing of cancer cells. This enabled them to identify which genes make tumours cells more or less vulnerable to immune attack.

Published today (20 January) in Cell Reports Medicine, the study sheds light on why some patients are more or less likely to respond to certain types of cancer treatments and could guide the development of more successful personalised treatments.

Immunotherapy works by harnessing a patient’s own immune system to fight cancer.1 It is used across different stages of cancer, from early to advanced disease, and is often given before surgery to shrink tumours or after to prevent recurrence of the disease.

There are different types of immunotherapies. One is called immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), which is used to “release the brakes” on the immune system, allowing immune cells to recognise and attack tumour cells.2 It is particularly effective for many cancer types such as melanoma and in tumours with faulty DNA repair systems, known as microsatellite instability (MSI).3 MSI cancers are highly responsive to immunotherapy because their defective DNA repair system creates many mutations, leading to lots of abnormal proteins that are easily detected and attacked by the immune system.

However, despite its success in some patients, the response rate of immunotherapy is below 35 per cent in people with solid tumours4 and scientists don’t fully understand why some tumours respond to the immune system while others resist it.

In a new study, Sanger Institute researchers and their collaborators looked for genes inside cancer cells that influence how well the immune system can attack tumours. The researchers applied a tool called genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 screening.5 This allowed them to switch off genes one-by-one across the entire genome to observe how cancer cells responded to immune signals.

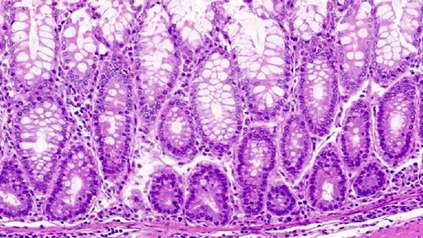

To measure the killing of cancer cells by immune cells, the researchers developed a new CRISPR method where tumour cells and immune cells from the same individual are cultured together, also known as a co-culture.6

The researchers discovered that two genes, CHD1 and MAP3K7, are key regulators of immune sensitivity. When either of these genes are knocked out, the cancer cells become more sensitive to the immune system – especially to key immune signals such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and to direct attack by T-cells, which are some of the most important cancer-killing immune cells.

When both genes were switched off at the same time, cancer cells became even more vulnerable. This suggests the loss of CHD1 and MAP3K7 changes how cancer cells respond to inflammatory signals, pushing them towards self-destruction when the immune system is activated.

The researchers then tested these findings in mouse models and found that tumours lacking these genes responded far better to immunotherapy as they attracted a higher level of cancer-killing immune cells.

Finally, analysis of patient data showed that cancers with low levels of CHD1 or MAP3K7 expression were more likely to respond to immunotherapy.7 Therefore, the researchers suggest that CHD1 and MAP3K7 could potentially help identify patients who are most likely to benefit from immunotherapy and open up new ways to improve personalised treatment, and outcomes, for people with cancer.

“We found that when cancer cells lose two genes, CHD1 and MAP3K7, they become much easier for the immune system to attack, as without these active genes, cancer cells respond very differently to immune signals. This loss exposes a weakness that immune cells can take advantage of.”

Alex Watterson, co-first author formerly at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, and now based at the Babraham Institute

“We saw that patients whose tumours have low expression of these genes are more likely to benefit from immunotherapy. In the future, these new biomarkers could guide doctors by predicting who will respond to treatment and enable more personalised cancer care.”

Dr Matthew Coelho, senior author at the Wellcome Sanger Institute and Open Targets

“Immunotherapy can be life-changing for some people with cancer, but for many patients it simply doesn’t work, and it’s been a mystery why that is the case. Understanding the mechanism behind why some tumours respond and others resist treatment is one of the biggest conundrums that our research is one step closer to helping to solve.”

Dr Mathew Garnett, co-senior author at the Wellcome Sanger Institute and Open Targets

More information

Notes

- Cancer Research UK. What is immunotherapy? Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/treatment/targeted-cancer-drugs-immunotherapy/what-is-immunotherapy [Last accessed: January 2026]

- Cancer Research UK. Checkpoint inhibitors. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/treatment/targeted-cancer-drugs-immunotherapy/checkpoint-inhibitors [Last accessed: January 2026]

- Pardoll, D.M. (2012). The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 12, 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3239.

- Morad, G., Helmink, B.A., Sharma, P., and Wargo, J.A. (2021). Hallmarks of response, resistance, and toxicity to immune checkpoint blockade. Cell 184, 5309–5337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.09.020.

- More information on CRISPR-Cas9 can be found here: https://www.yourgenome.org/theme/what-is-crispr-cas9/

- The source of the cell lines and organoids can be found in the Key Resource table in the publication.

- Patient records were from the Hartwig Medical Foundation, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Publication

A. Watterson et al. (2026) ‘CRISPR screens in the context of immune selection identify CHD1 and MAP3K7 as mediators of cancer immunotherapy resistance’. Cell Reports Medicine. DOI: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2025.102565

Funding

This research was supported in part by Wellcome, Open Targets, Cancer Research UK and a Wellcome Sanger Institute Accelerator Award for Postdocs. A full list of funders and acknowledgement can be found in the publication.