Order of cancer-driving mutations affects the chance of tumour development

The order of cancer-driving mutations — genetic changes — plays an important role in whether tumours in the intestine can develop, new research reveals.

These are the findings published on 3 December in Nature, from researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute, University of Glasgow and their collaborators. Using intestinal cells from mice models, the team used two approaches that involved exposing the cells to a compound that causes random mutations.

By revealing how the order of mutations drives tumour growth, these insights could inform treatment and prevention strategies that target the earliest steps of cancer development.

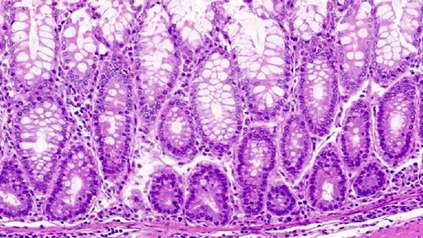

Colorectal cancer – also known as bowel cancer – can be found anywhere in the large bowel, which includes the colon and rectum. It is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and accounts for approximately 10 per cent of all cancer cases.1 Colorectal cancers were commonly thought to develop when cells accumulate mutations in a sequence of cancer-promoting genes such as APC, KRAS, and TP53. In this model, an initial mutation in APC is followed by additional mutations that further help a tumour to grow.

However, recent studies have questioned this simple progression. Cancer-promoting mutations have been found in normal intestinal tissue, and some tumours appear to form through cooperation between neighbouring cells carrying different APC mutations.

In a new study to investigate these patterns more closely, researchers at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute, Sanger Institute and their collaborators, examined how the timing and sequence of mutations affect the earliest stages of tumour development. Using mouse models, the team tested two complementary approaches.

In the first approach, the team introduced specific cancer-driving mutations into intestinal cells, then exposed tissue to N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU), a compound that induces random mutations.

In the second approach, ENU was used to create a range of random mutations first before the team then switched on the specific cancer-driving mutations at controlled time points.

By comparing outcomes, they showed that mutations do not act in isolation. Instead, their effects depend heavily on the genetic environment in which they happen.

The study found that many intestinal cells that do carry cancer-driving mutations are then removed through strong negative selection. Only a small minority survive long enough to influence the future development of a tumour.

Importantly, some mutations, including certain mutations of the gene APC, appeared to disadvantage cell survival unless they happened after other mutations had already taken place. This suggests that earlier mutations can shape the tissue environment in ways that can then influence whether later cancer-driving mutations are able to push a cell towards becoming cancerous.

Though more research is needed to understand how this applies in humans, the findings show that early genetic changes can have a significant influence on cancer risk. These insights into how mutation order affects tumour development may help direct future treatment and prevention strategies towards the earliest stages of tumour initiation.

“This study shows that some mutational events previously thought to occur later in cancer evolution are actually critical for the survival of cells harbouring the tumour-initiating mutations. My future research will focus on understanding why these initiating mutations are negatively selected unless supported by other driver mutations, and on uncovering the nature of these interactions. Together, this will help clarify the early evolutionary steps that lead to tumour formation.”

Dr Filipe Lourenco, first author and Research Associate at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute

“The fact that many of the most common colorectal cancer mutations are removed by negative selection highlights how vulnerable they actually are. Our findings suggest that these drivers only succeed once earlier mutations have altered the tissue environment. That raises the possibility that prevention efforts could focus on limiting the growth of those early changes, rather than targeting the mutations that appear most powerful in the disease.”

Professor Doug Winton, senior author and Senior Group Leader at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute

“This work has helped us understand how early genetic changes influence tumour development and subsequently cancer risk. We hope it can provide a useful stepping stone for having a deeper understanding of colorectal cancer in humans and bring us closer to preventing this deadly cancer at the earliest possible stage.”

Dr David Adams, co-author and Senior Group Leader at the Wellcome Sanger Institute

More information

Notes

- World Health Organisation. Colorectal cancer. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/colorectal-cancer [Last accessed: December 2025]

Publication

Filipe C. Lourenço et al. (2025) ‘Decay of driver mutations shapes the landscape of intestinal transformation’. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09762-w

Funding

The research was supported in part by Cancer Research UK, Wellcome, Innovate UK and Beatson Cancer Charity. The full list of acknowledgements can be found in the publication.