Never too late to quit: protective cells could cut risk of lung cancer for ex-smokers

Protective cells in the lungs of ex-smokers could explain why quitting smoking reduces the risk of developing lung cancer, scientists have determined. Researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, UCL and their collaborators have discovered that, compared to current smokers, people who had stopped smoking had more genetically healthy lung cells, which have a much lower risk of developing into cancer.

The research, published in Nature today (Wednesday 29th January), is part of the £20 million Mutographs of Cancer project, a Cancer Research UK Grand Challenge initiative. The project detects DNA ‘signatures’ that indicate the source of damage, to better understand the causes of cancer, and discover the ones we may not yet be aware of.

The study shows that quitting smoking could do much more than just stopping further damage to the lungs. Researchers believe it could also allow new, healthy cells to actively replenish the lining of our airways. This shift in proportion of healthy to damaged cells could help protect against cancer.

These results highlight the benefits of stopping smoking completely, at any age.

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer death in the UK, accounting for 21 per cent of all cancer deaths.* Smoking tobacco damages DNA and hugely increases the risk of lung cancer, with around 72 per cent of the 47,000 annual lung cancer cases in the UK caused by smoking.**

Damage to the DNA in cells lining the lungs creates genetic errors, and some of these are ‘driver mutations’, which are changes that give the cell a growth advantage. Eventually, an accumulation of these driver mutations can let the cells divide uncontrollably and become cancerous. However, when someone stops smoking, they avoid most of the subsequent risk of lung cancer.***

In the first major study of the genetic effects of smoking on ‘normal’, non-cancerous lung cells, researchers analysed lung biopsies**** from 16 people including smokers, ex-smokers, people who had never smoked and children.

They sequenced the DNA of 632 individual cells from these biopsies and looked at the pattern of genetic changes in these non-cancerous lung cells.

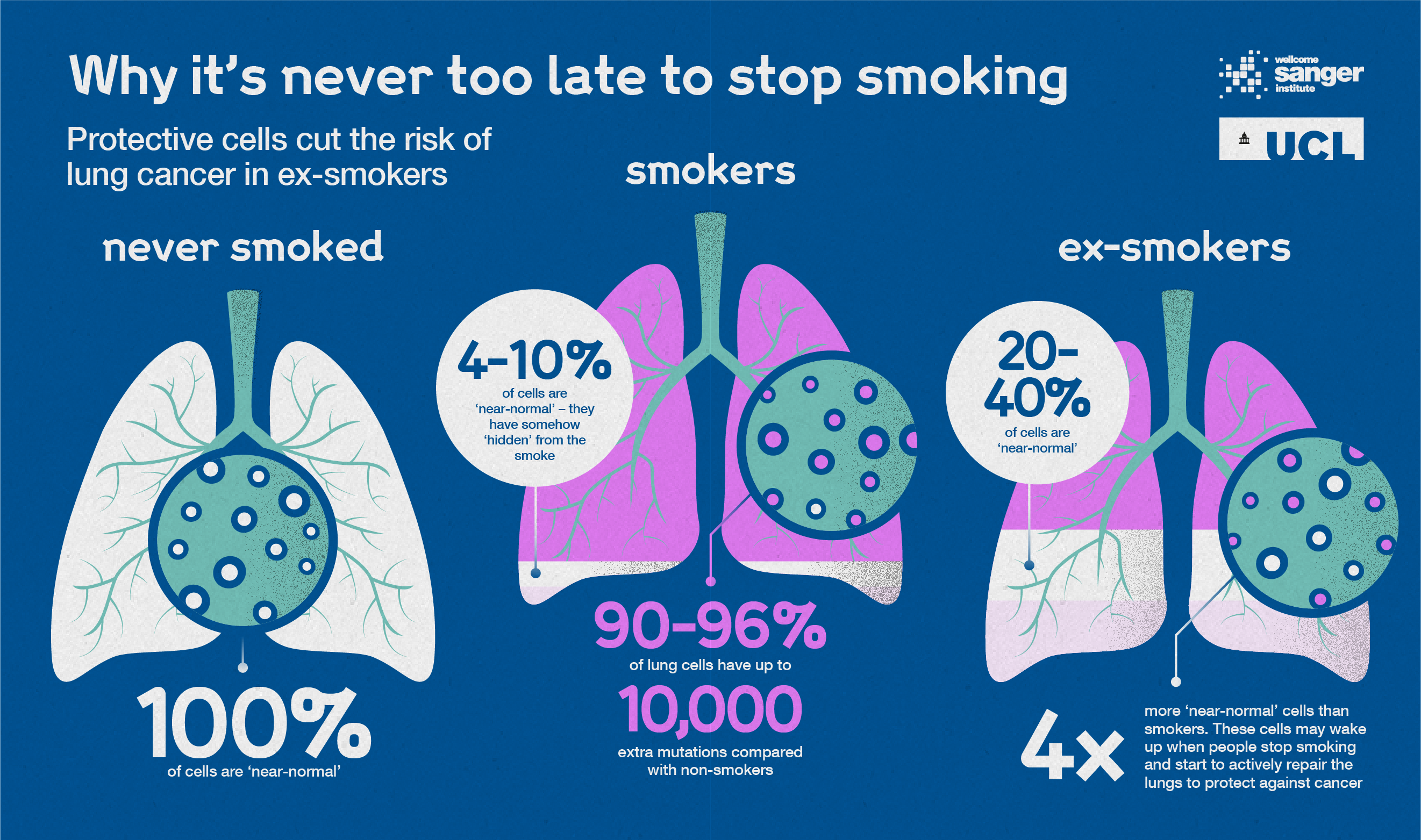

The researchers found that despite not being cancerous, more than 9 out of every 10 lung cells in current smokers had up to 10,000 extra genetic changes – mutations – compared with non-smokers, and these mutations were caused directly by the chemicals in tobacco smoke. More than a quarter of these damaged cells had at least one cancer-driver mutation, which explains why the risk of lung cancer is so much higher in people who smoke.

Unexpectedly, in people who had stopped smoking, there was a sizable group of cells lining the airways that had escaped the genetic damage from their past smoking. Genetically, these cells were on par with those from people who had never smoked: they had much less genetic damage from smoking and would have a low risk of developing into cancer.

The researchers found that ex-smokers had four times more of these healthy cells than people who still smoked – representing up to 40 per cent of the total lung cells in ex-smokers.

“People who have smoked heavily for 30, 40 or more years often say to me that it’s too late to stop smoking – the damage is already done. What is so exciting about our study is that it shows that it’s never too late to quit – some of the people in our study had smoked more than 15,000 packs of cigarettes over their life, but within a few years of quitting many of the cells lining their airways showed no evidence of damage from tobacco.”

Joint senior author Dr Peter Campbell, from the Wellcome Sanger Institute

“Our study is the first time that scientists have looked in detail at the genetic effects of smoking on individual healthy lung cells. We found that even these healthy lung cells from smokers contained thousands of genetic mutations. These can be thought of as mini time-bombs waiting for the next hit that causes them to progress to cancer. Further research with larger numbers of people is needed to understand how cancer develops from these damaged lung cells.”

Dr Kate Gowers, joint first author from UCL

While the study showed that these healthy lung cells could start to repair the lining of the airways in ex-smokers and help protect them against lung cancer, smoking also causes damage deeper in the lung that can lead to emphysema – chronic lung disease. This damage is not reversible, even after stopping smoking.

“Our study has an important public health message and shows that it really is worth quitting smoking to reduce the risk of lung cancer. Stopping smoking at any age does not just slow the accumulation of further damage, but could reawaken cells unharmed by past lifestyle choices. Further research into this process could help to understand how these cells protect against cancer, and could potentially lead to new avenues of research into anti-cancer therapeutics.”

Professor Sam Janes, joint senior author from UCL and University College London Hospitals Trust

“It’s a really motivating idea that people who stop smoking might reap the benefits twice over – by preventing more tobacco-related damage to lung cells, and by giving their lungs the chance to balance out some of the existing damage with healthier cells. What’s needed now are larger studies that look at cell changes in the same people over time to confirm these findings.

“The results add to existing evidence that, if you smoke, stopping completely is the best thing you can do for your health. It’s not always easy to kick the habit, but getting support from a free, local Stop Smoking Service roughly triples the chance of success compared to going it alone.”

Dr Rachel Orritt, Health Information Manager at Cancer Research UK

More information

Publication:

Kenichi Yoshida and Kate Gowers et al. (2019). Tobacco exposure and somatic mutations in normal human bronchial epithelium. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-1961-1

Notes to editors:

* Data were provided by: the Office for National Statistics on request, November 2018; ISD Scotland on request, October 2018; the Northern Ireland Cancer Registry on request, March 2019

** Calculated by the Statistical Information Team at Cancer Research UK, 2018. Based on Brown KF, Rumgay H, Dunlop C, et al. The fraction of cancer attributable to known risk factors in England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and the UK overall in 2015. British Journal of Cancer 2018; and incidence data were provided by the National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service (part of Public Health England), on request through the Office for Data Release, August 2018; ISD Scotland on request, April 2018; the Welsh Cancer Intelligence and Surveillance Unit, Health Intelligence Division, Public Health Wales on request, February 2019; the Northern Ireland Cancer Registry on request, April 2018

***Lung cancer risk, particularly squamous cell carcinoma risk, is much lower in people who used to smoke compared with people who currently smoke, and the gap widens as time since quitting smoking increases. Lung cancer risk in people who used to smoke who quit around 7 years previously is 43 per cent lower compared with current smokers. Lung cancer risk in ex-smokers who quit around 12 years previously is 72 per cent lower compared with people who currently smoke.

Lee PN, Forey BA, Coombs KJ. Systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence in the 1900s relating smoking to lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012 Sep 3; 12: 385.

**** Patients donated tissue from bronchoscopy investigations for other issues. The bronchial epithelium tissue used in this study was normal rather than diseased tissue.

Funding:

This work was supported by Wellcome (WT088340MA) (WT209199/Z/17/Z), Cancer Research UK, [C98/A24032] (C57387/A21777), the MRC (MR/R015635/1), the Longfonds BREATH lung regeneration consortium, the Rosetrees Trust, the Stoneygate Trust, the British Lung Foundation, the UCLH Charitable Foundation, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research and the Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation and the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre.

Selected websites

About Cancer Research UK

- Cancer Research UK is the world’s leading cancer charity dedicated to saving lives through research.

- Cancer Research UK’s pioneering work into the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of cancer has helped save millions of lives.

- Cancer Research UK receives no funding from the UK government for its life-saving research. Every step it makes towards beating cancer relies on vital donations from the public.

- Cancer Research UK has been at the heart of the progress that has already seen survival in the UK double in the last 40 years.

- Today, 2 in 4 people survive their cancer for at least 10 years. Cancer Research UK’s ambition is to accelerate progress so that by 2034, 3 in 4 people will survive their cancer for at least 10 years.

- Cancer Research UK supports research into all aspects of cancer through the work of over 4,000 scientists, doctors and nurses.

- Together with its partners and supporters, Cancer Research UK’s vision is to bring forward the day when all cancers are cured.

For further information about Cancer Research UK’s work or to find out how to support the charity, please call 0300 123 1022 or visit www.cancerresearchuk.org. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

About UCL – London’s Global University

UCL is a diverse community with the freedom to challenge and think differently. Our community of more than 41,500 students from 150 countries and over 12,500 staff pursues academic excellence, breaks boundaries and makes a positive impact on real world problems. We are consistently ranked among the top 10 universities in the world and are one of only a handful of institutions rated as having the strongest academic reputation and the broadest research impact. We have a progressive and integrated approach to our teaching and research – championing innovation, creativity and cross-disciplinary working. We teach our students how to think, not what to think, and see them as partners, collaborators and contributors. For almost 200 years, we are proud to have opened higher education to students from a wide range of backgrounds and to change the way we create and share knowledge. We were the first in England to welcome women to university education and that courageous attitude and disruptive spirit is still alive today. We are UCL.

About UCLH

UCLH (University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust) provides first-class acute and specialist services in five hospitals in North Central London. These include University College Hospital and the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery. UCLH is committed to education and research and forms part of UCLPartners which in March 2009 was officially designated as one of the UK’s first academic health science centres by the Department of Health. UCLH works closely with UCL, translating research into treatments for patients.

Please see our website www.uclh.nhs.uk for more information, we are also on Facebook (UCLHNHS), Twitter (@uclh), Youtube (UCLHvideo) and Instagram (@uclh).

National Institute for Health Research

This research was supported by the NIHR University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre.

The NIHR is the nation’s largest funder of health and care research. The NIHR:

- Funds, supports and delivers high quality research that benefits the NHS, public health and social care

- Engages and involves patients, carers and the public in order to improve the reach, quality and impact of research

- Attracts, trains and supports the best researchers to tackle the complex health and care challenges of the future

- Invests in world-class infrastructure and a skilled delivery workforce to translate discoveries into improved treatments and services

- Partners with other public funders, charities and industry to maximise the value of research to pa-tients and the economy

The NIHR was established in 2006 to improve the health and wealth of the nation through research, and is funded by the Department of Health and Social Care. In addition to its national role, the NIHR commissions applied health research to benefit the poorest people in low- and middle-income countries, using Official Development Assistance funding.

The Wellcome Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Sanger Institute is a world leading genomics research centre. We undertake large-scale research that forms the foundations of knowledge in biology and medicine. We are open and collaborative; our data, results, tools and technologies are shared across the globe to advance science. Our ambition is vast – we take on projects that are not possible anywhere else. We use the power of genome sequencing to understand and harness the information in DNA. Funded by Wellcome, we have the freedom and support to push the boundaries of genomics. Our findings are used to improve health and to understand life on Earth.

Find out more at scion-02.sandbox.sanger.ac.uk or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and on our Blog.

About Wellcome

Wellcome exists to improve health by helping great ideas to thrive. We support researchers, we take on big health challenges, we campaign for better science, and we help everyone get involved with science and health research. We are a politically and financially independent foundation. https://wellcome.org/