Detailed cell map unlocks secrets of how reproductive organs form

New research has mapped the cell types that specialise to form reproductive organs in both sexes, identifying key genes and signals that drive this process. The findings offer important insights into conditions affecting the reproductive organs, and how environmental chemicals may affect reproductive health.

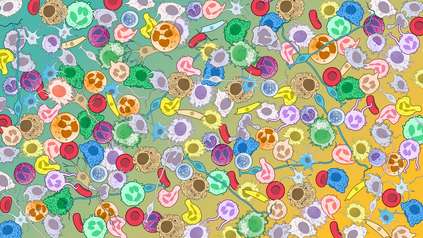

Researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute and EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) used a combination of single-cell and spatial genomics technologies to analyse over half a million individual human cells from the developing reproductive system.

Published today (17 December) in Nature, the study provides the most detailed picture to date of how reproductive organs form in the womb, uncovering crucial biological pathways that shape their development.

Although chromosomal sex (XX or XY) is determined at conception, visible differences in the developing reproductive system do not appear until about six weeks later. At this stage, all embryos have undifferentiated gonads as well as the same paired structures — the Müllerian ducts and the Wolffian ducts — which have the potential to form the female or male internal reproductive organs. A gene on the Y chromosome called SRY triggers the undifferentiated gonads to develop into the testes; the testes then produce hormones that guide the Wolffian ducts to form male reproductive structures and cause the Müllerian ducts to regress. In the absence of SRY, the gonads become ovaries and the Müllerian ducts develop into female reproductive organs.

While development of the testes and ovaries in humans has been mapped at the cellular and molecular level in detail due to their importance in fertility,1 the development of the rest of the reproductive system has been far less understood, until now.

In a new study, researchers at the Sanger Institute and EMBL-EBI analysed over half a million individual cells from 89 donated embryonic and fetal tissue samples,2 in order to look at what genes and signals underpin the differentiation of the male and female reproductive tract. The study is part of the Human Cell Atlas initiative which is mapping all cell types in the body to understand health and disease.3

The team used single-cell RNA sequencing to measure which genes are switched on in each cell, and single-cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin (ATAC) sequencing, which identifies regions of DNA that are potentially active. They also used spatial transcriptomics to show where exactly within a tissue section those genes are switched on. This combination of approaches enabled the researchers to build a detailed, cell-by-cell map of how the initially simple Müllerian and Wolffian ducts remodel into distinct, connected organs (like the fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix and vagina, or epididymis, vas deferens and seminal vesicle), each with its own shape and function.

Firstly, the scientists uncovered the genes that help the Müllerian duct mature in females, and other genes that are likely to trigger its breakdown in males. In the developing external genitals, they traced how the formation of the urethra differs between males and females, offering new clues about the causes of hypospadias, a condition where the urethra opens partway along the penis instead of at the tip.

Next, the researchers mapped changes in gene activity in the Müllerian and Wolffian ducts. To do this, they built a computational model that allowed the tracking of genes that are switched on or off along the length of these ducts as they grow. This revealed gradual, region-by-region shifts in gene activity and identified specific signalling pathways that help divide the ducts into distinct organs. As a result, the study proposes an updated model of how the HOX code shapes reproductive organs, revealing previously unreported HOX genes that pattern the upper fallopian tube and epididymis.4

Finally, the team looked into how vulnerable developing reproductive tissues are to environmental disruption using tiny 3D models (known as organoids) of the developing uterine lining. When exposed to compounds such as bisphenol A (BPA) and butyl benzyl phthalate — which are both linked to health concerns — the organoids switched on oestrogen-responsive genes.5 This confirms that the fetal uterine lining can initiate a genetic response to environmental oestrogens. However, the researchers note that it remains unclear what levels of these compounds the reproductive system is exposed to in real-world maternal conditions.

By creating this high-resolution atlas of the developing reproductive system, the researchers have provided a strong foundational reference map for how reproductive organs develop — offering new clues into how reproductive disorders arise.

“For the first time, we can see in detail how the human reproductive system is assembled before birth. This map pinpoints the exact cells and signals that shape each organ, and highlights when development is most vulnerable. This is an essential step towards understanding fertility, congenital alterations, and the impact of our environment on reproductive health.”

Dr Valentina Lorenzi, co-first author at the Wellcome Sanger Institute and EMBL-EBI

“Capturing where each signal occurs is just as important as knowing what it is. By preserving spatial information, we can watch regionalisation unfold, seeing how the Müllerian and Wolffian ducts are patterned along their length and then transformed into distinct organs.”

Dr Cecilia Icoresi-Mazzeo, co-first author at the Wellcome Sanger Institute

“A major challenge in gynaecology has been that we lacked a clear roadmap of how reproductive tissues form, making many conditions difficult to diagnose. Our work provides that roadmap, helping us trace genetic disruptions and understand the developmental origin of histological abnormalities.”

Dr Luz Garcia-Alonso, co-senior author at the Wellcome Sanger Institute

“Many conditions affecting fertility and reproductive health have their roots in development before birth, yet until now we lacked a full picture of how these organs form in humans. Our atlas offers that missing piece, providing a powerful resource for both basic science and clinical research.”

Dr Roser Vento-Tormo, senior author at the Wellcome Sanger Institute

More information

Notes to Editors

- Luz Garcia-Alonso et al. (2022) ‘Single-cell roadmap of human gonadal development’. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04918-4.

- The human embryonic and foetal material was provided by the Joint MRC / Wellcome Trust Human Developmental Biology Resource (HDBR, http:// www.hdbr.org), with appropriate maternal written consent and Ethics approval. The HDBR is regulated by the UK Human Tissue Authority (HTA; www.hta.gov.uk) and operates in accordance with the relevant HTA Codes of Practice.

- This study is part of the international Human Cell Atlas (HCA) consortium, which is creating comprehensive reference maps of all human cells as a basis for both understanding human health and diagnosing, monitoring, and treating disease. The HCA is an international collaborative consortium whose mission is to create comprehensive reference maps of all human cells – the fundamental units of life – as a basis for understanding human health and for diagnosing, monitoring, and treating disease. The HCA community is producing high-quality Atlases of tissues, organs and systems, to create a milestone Atlas of the human body. More than 4,000 HCA members from over 100 countries are working together to achieve a diverse and accessible Atlas to benefit humanity across the world. Discoveries are already informing medical applications from diagnoses to drug discovery, and the Human Cell Atlas will impact every aspect of biology and healthcare, ultimately leading to a new era of precision medicine. https://www.humancellatlas.org

- Regional patterns of the body are guided in part by the HOX code. The HOX code is a set of genes that gives cells positional “addresses”, telling them where to form along the body during development.

- Bisphenol A (BPA) is a synthetic chemical used to make polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins, found in food and drink cans, water bottles, and food storage containers. Butyl benzyl phthalate (BBP) is an oily liquid phthalate used as a plasticiser to make plastics flexible, found in products like vinyl flooring, adhesives, and sealants.

Publication

V. Lorenzi, C. Icoresi-Mazzeo, et al. (2025) ‘Spatiotemporal cellular map of the developing human reproductive tract’. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09875-2

Funding

This research was supported in part by Wellcome and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme.