River blindness worm’s genome reveals unique fatal flaws

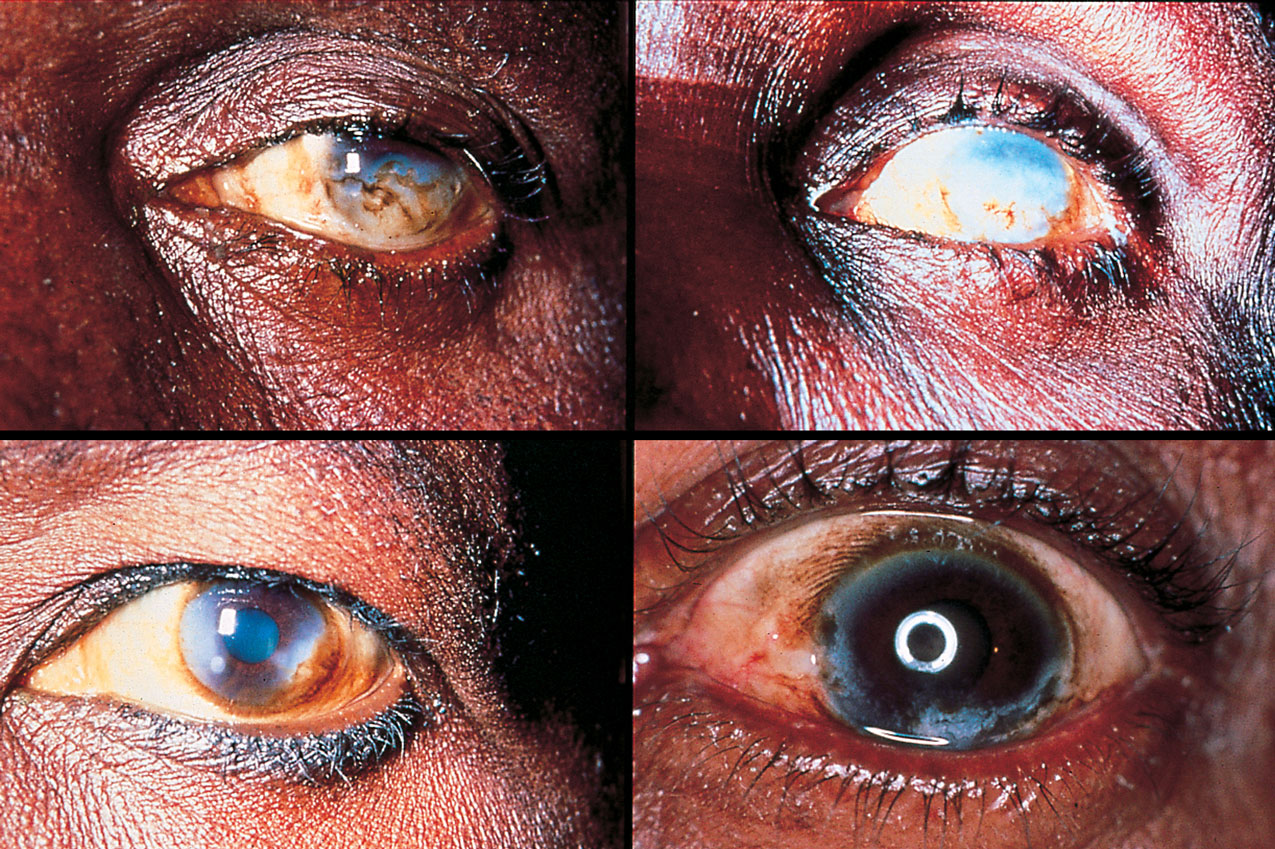

River blindness is a common chronic infectious neglected disease that blights many communities near water in remote areas of the Amazon basin in South America and in Africa. It is caused by the worm Onchocerca volvulus, whose larvae migrate through the body, including into the eyes of infected people, making them blind.

The parasite is a major socioeconomic issue in the villages and families it affects because sufferers are no longer able to work. In addition other family members, often children, have to give up their studies or work to care for them, further depriving the family of income or future development.

Efforts to control Onchocerca rely almost exclusively on a single drug – ivermectin – which has become so important it’s discoverers shared the Nobel prize for medicine last year. However, treatment has a potentially fatal side-effect.

In many places people are infected with two species of worm at the same time: Onchocerca and its evolutionary near neighbour Loa Loa. Ivermectin not only kills Onchocerca, it also kills Loa – which is often fairly benign and does not affect people too seriously – but killing it can provoke a serious immune reaction (anaphylactic shock) which can kill the patient.

“One problem with eradicating river blindness is that we need a way to kill the Onchocerca infection without killing coinfecting Loa Loa and provoking a fatal immune reaction. What we need is a magic bullet that will only target Onchocerca.”

Dr James Cotton First author of the study, from the Sanger Institute

To help find the magic bullet, Sanger Institute researchers and colleagues at the New York Blood Center and the US National Institutes of Health have read the entire genome of Onchocerca to understand how it works and discover how it differs from its evolutionary neighbour.

“We now have the full map of the river blindness worm from end to end. This is vital because it not only shows what is in the genome, but also what is missing in comparison with Loa Loa. These key differences show us how the biological pathways within the two species’ differ, giving us important ways to target Onchocerca, and leave Loa Loa untouched.”

Dr Matt Berriman Joint senior author of the study and member of Faculty at the Sanger Institute

One reason why the two species of worm differ is that Onchocerca carries a bacterial passenger in its cells – an endosymbiont. Loa Loa does not. As the bacteria and Onchocerca developed their symbiotic relationship, the worm evolved to rely on the bacteria to supply some of its needs, by losing the genes to make some molecules. Now, if the bacteria die, the worm dies too. These missing genes offer an exciting opportunity to target the worm.

One key difference lies in the worm’s ability to produce purines. The team worked with ChEMBL (a database of bioactive small drug-like molecules) to match these genetic changes to already existing drugs. They discovered a number of drugs that already have licenses for other uses that could be investigated and trialled.

Another possible line of attack offered by the worm’s genome lies in the unusually large number of genes for a particular step in synthesising collagen that Onchocerca has. The worm has a protective cuticle – a coat largely made from collagens – but this does not explain why it has so many genes. One theory is that it could be something to do with the parasite needing to change it coat as it grows and passes through people and the insect (a biting fly) that transmits it.

The team hope that this mysterious reliance on having so many genes to make collagens will turn out to be a weakness that could also be targeted. Drugs targeting these kinds of gene are already in development for treating collagen-based conditions, and they may be useful in preventing river blindness too.

More information

Publications:

Selected websites

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is one of the world’s leading genome centres. Through its ability to conduct research at scale, it is able to engage in bold and long-term exploratory projects that are designed to influence and empower medical science globally. Institute research findings, generated through its own research programmes and through its leading role in international consortia, are being used to develop new diagnostics and treatments for human disease.

Wellcome

Wellcome exists to improve health for everyone by helping great ideas to thrive. We’re a global charitable foundation, both politically and financially independent. We support scientists and researchers, take on big problems, fuel imaginations and spark debate.