Prostate cancer study overturns thinking on cancer's spread

In a study that overturns previous thinking about how human cancers spread, researchers have discovered that multiple cancerous cells can spread from a primary tumour in the prostate to the same new location in the body. The study recorded patterns of spread from primary prostate tumours to secondary tumours through a process called metastasis, which causes 90 per cent of cancer-related deaths.

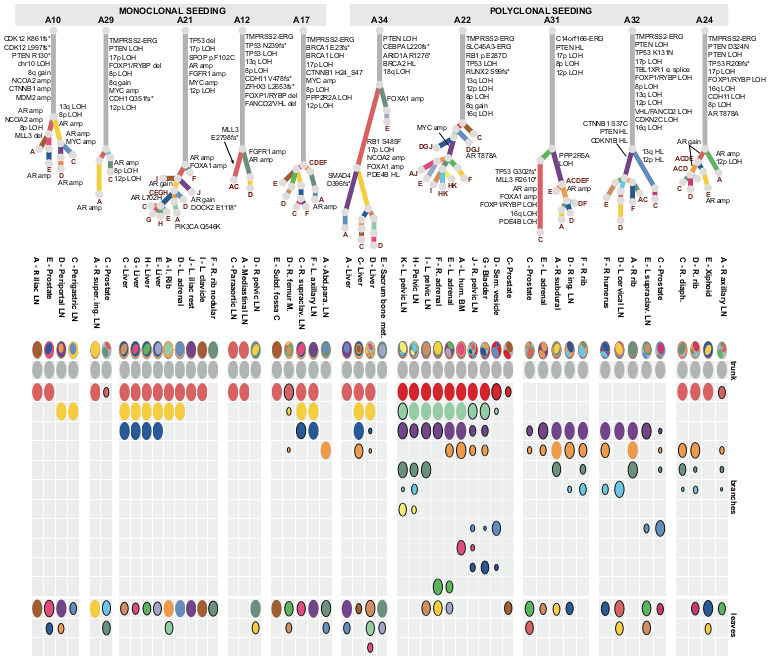

Cancers often have several regions containing sets of cells with different sets of mutations, known as clones. Previously, it was thought that secondary tumours, metastases, were formed when a single newly mutated cancer cell breaks away from the primary tumour. However, this study found that, in half of the patients studied, cells from two or three different clones broke away from the tumour and travelled to the same location in another tissue to form a new polyclonal tumour. Polyclonal seeding has been previously observed in studies with mouse models but this is the first time it has been reported in human cancer.

“We know very little of the principles that govern metastasis but our results suggest that this process of polyclonal seeding at different organ sites is a common occurrence in metastatic prostate cancer. By tracking patterns of spread, we hope to identify the often fatal initiation of polyclonal metastases and learn how they can be prevented from forming.”

Dr Gunes Gundem First author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

Whole-genome sequencing was used to identify an average of 20,000 mutations in each of the 51 tumour samples taken from 10 prostate cancer patients who had developed metastases and died from the disease. Similar mutations were grouped into clones to produce a family tree, called a phylogenetic tree, showing how the clones are related to one another. These relationships provide researchers with an insight into how cancers evolve and spread.

The researchers noticed that all of the clones, no matter what organ of the body they seeded in, retained genetic imprints of their ancestors in the primary tumour. All of the patients studied were treated with androgen deprivation therapy, a treatment that deprives cells of a signal that instructs the prostate to grow during normal development and is hijacked by cancer cells. Researchers found that many of the metastases accumulated convergent genetic alterations related to resistance to androgen-ablation therapy and hence were still dependent on androgen signalling even if they were no longer in the prostate. This finding suggests that targeted treatments used to battle the primary tumour may also have beneficial therapeutic effects on the subsequent metastases.

“Looking at the evolutionary history of these prostate cancers raises fascinating questions about how clones develop their ability to move to other tissues and why some are seeding in the same place. Also, a big question we have yet to answer is whether these multiple clones are cooperating in their new locations or whether they are competing.”

Dr David Wedge Senior author from the Sanger Institute

Once clones from the primary cancer have metastasised, a rapid expansion can be seen, with multiple metastases forming in quick succession. Researchers now need to investigate beyond genetics to understand all the mechanisms governing the patterns of spread that have been observed.

“In the phylogenetic trees that our data have produced, we see that most of the oncogenic mutations are shared clonally by all the tumour sites in each patient. This common genetic heritage is a potential achilles heel of the metastases, however, many of these shared mutations are in tumour suppressor genes and our approach to therapeutically targeting these needs to be prioritised. It takes a while before a tumour develops the ability to metastasise but once it does the patient’s prognosis changes significantly. We have to zoom in on this crucial junction and gather more data on the impact different therapies have on prostate cancer’s evolution and spread.”

Dr Ultan McDermott Senior author at the Sanger Institute

More information

Funding

Cancer Research UK (2011-present), Academy of Finland (2011-present), Cancer Society of Finland (2013-present), PELICAN Autopsy Study family members and friends (1998-2004), John and Kathe Dyson (2000), US National Cancer Institute CA92234 (2000-2005), American Cancer Society (1996-2000), Johns Hopkins University Department of Pathology (1997-2011), Women’s Board of Johns Hopkins Hospital (1998), The Grove Foundation (1998), Association for the Cure of Cancer of the Prostate (1994-1998), American Foundation for Urologic Disease (1991-1994), Bob Champion Cancer Trust (2013-present), Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO), European Hematology Association.

Participating Centres

Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, KU Leuven, University of East Anglia, University of Tampere and Tampere University Hospital, Johns Hopkins University, National Institutes of Health, University of Liverpool and HCA Pathology Laboratories, The Institute Of Cancer Research, University of Cambridge, Cancer Research UK Cambridge Research Institute, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, ICGC Prostate Cancer Project

Publications:

Selected websites

About Cancer Research UK

- Cancer Research UK is the world’s leading cancer charity dedicated to saving lives through research.

- Cancer Research UK’s pioneering work into the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of cancer has helped save millions of lives.

- Cancer Research UK receives no government funding for its life-saving research. Every step it makes towards beating cancer relies on every pound donated.

- Cancer Research UK has been at the heart of the progress that has already seen survival rates in the UK double in the last forty years.

- Today, 2 in 4 people survive cancer. Cancer Research UK’s ambition is to accelerate progress so that 3 in 4 people will survive cancer within the next 20 years.

- Cancer Research UK supports research into all aspects of cancer through the work of over 4,000 scientists, doctors and nurses.

- Together with its partners and supporters, Cancer Research UK’s vision is to bring forward the day when all cancers are cured.

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is one of the world’s leading genome centres. Through its ability to conduct research at scale, it is able to engage in bold and long-term exploratory projects that are designed to influence and empower medical science globally. Institute research findings, generated through its own research programmes and through its leading role in international consortia, are being used to develop new diagnostics and treatments for human disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.