Oblivious Oblivion

New research, published date in PLoS Genetics has defined a mutation in the mouse genome that closely mimics progressive hearing loss in humans. Extensive biological study of the mutants shows problems with the function of the sensory cells (hair cells) in the inner ear that ties in to hearing loss and occurs before clear physical effects are seen.

Progressive loss of hearing is common and affects around six out of ten people over the age of 70. Hearing deficits become more common in humans from birth onwards, with rates doubling from birth to age ten. Whilst it is clear that the environment – physical damage to the ear, exposure to excessive noise levels, drugs, infections and so on – can lead to hearing loss, genetic influences can also play a major role.

Remarkably, we know relatively little of the genes involved in common forms of progressive hearing loss. Although we know of many genes involved in deafness in childhood, most of these genes contribute only rarely to hearing loss in humans and their role in progressive hearing loss is poorly understood.

“This is part of a systematic approach to identifying genes that play a role in hearing and deafness. We know of only a handful of gene variants involved in progressive hearing loss, identified over the past 15 years. We need a better approach to understanding hearing loss: this is one of the first fruits of that programme.”

Professor Karen Steel from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and senior author on the study

In the new research The team systematically examined mice for an impaired hearing response. One mouse mutation, called Oblivion, showed some features in common with forms of human deafness. If both copies of the Oblivion gene were mutant, the mice were completely deaf from birth. However, if a non-mutant form was inherited from one parent and a mutant form from the other, the mice show progressive hearing loss during the first three months of life.

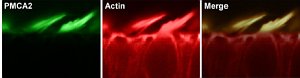

The team worked with colleagues in Munich and Padua to study the biology of the hearing responses and the structure of the cells in the ear, where structures transmit sound and help to control our balance. Delicate ‘hair’ cells help to transmit sound and turn it into electrical impulses that our brain can interpret.

In mice with one mutant copy of the gene the hair cells showed some function at first but later degenerated: in mice with two mutant copies the hair cells were already damaged when born.

“When we mapped the mutation to the mouse genome, we quickly found a probable cause for hearing loss. We showed that the mutant mice carried a change in one letter of their genetic code in a gene called Atp2b2. Changing a specific C to a T in this gene stops it from producing a normal molecular pump that is needed to keep hair cells in the ear working efficiently by pumping excess calcium out of the cell.

“If one copy of the gene is affected, the pump works, but not well enough and hearing gradually fails; if both copies are affected, the pump hardly works at all and hearing is lost before birth.”

Professor Karen Steel from the Sanger Institute

Although other mutations have been described, Oblivion is unique in the way it leads to hearing loss due to mutations in Atp2b2. The deficits in hearing are seen before any physical sign can be seen of damage to the hair cell. The effect mimics human progressive loss of hearing. Indeed, some instances of human hearing loss are due, at least in part, to mutation in the human Atp2b2 gene.

“One aim of identifying and characterizing mice with impaired hearing is to help us to understand the biology of this remarkable sense. Improving our understanding of the molecular and cellular action of genetic variants will help us to develop improved diagnostics and improved treatments for humans.”

Professor Karen Steel from the Sanger Institute

More information

Publications:

Selected websites

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, which receives the majority of its funding from the Wellcome Trust, was founded in 1992. The Institute is responsible for the completion of the sequence of approximately one-third of the human genome as well as genomes of model organisms and more than 90 pathogen genomes. In October 2006, new funding was awarded by the Wellcome Trust to exploit the wealth of genome data now available to answer important questions about health and disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.