Red hair gene variant drives up skin cancer mutations

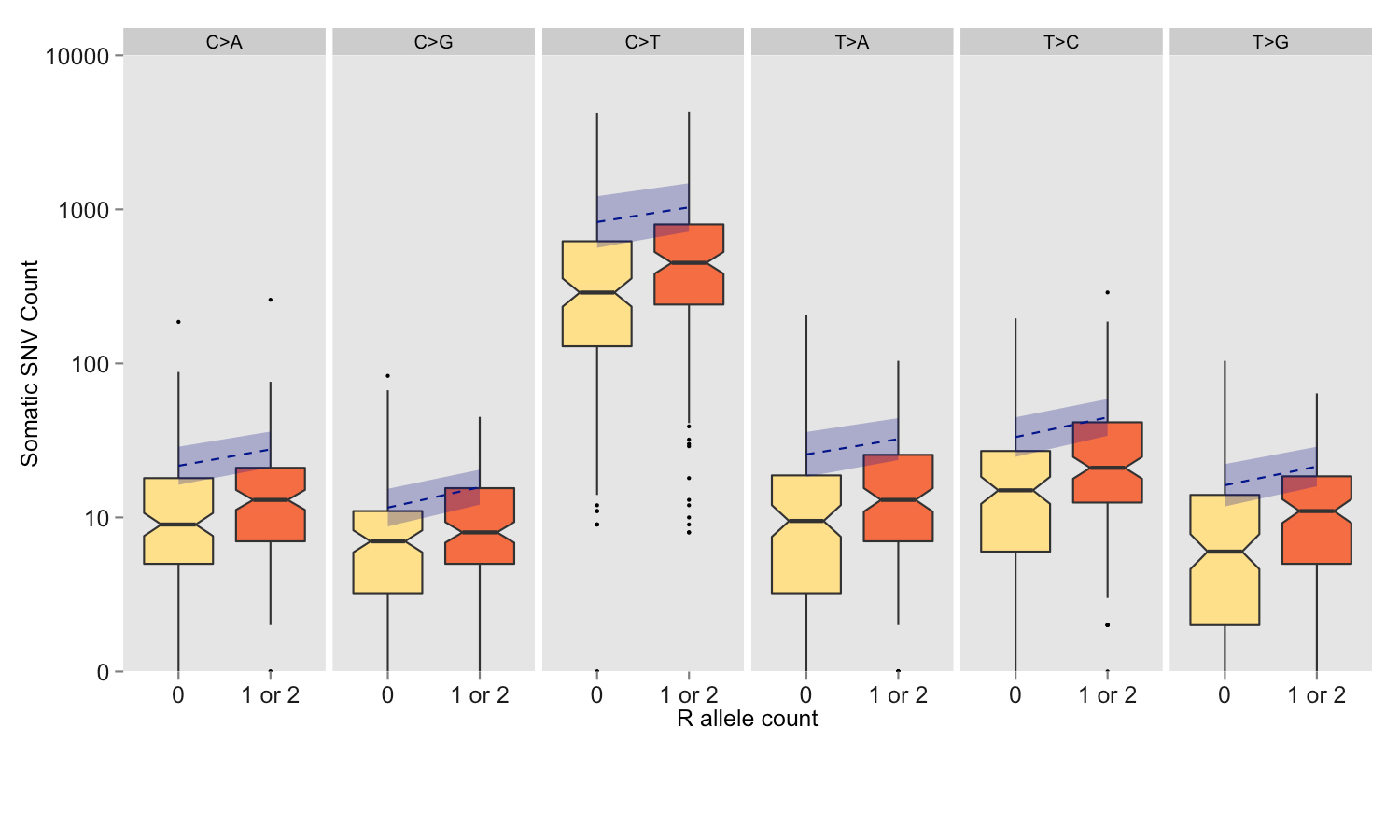

The research, published today (Tuesday 12 July) in Nature Communications, showed that even a single copy of a red hair-associated MC1R gene variant increased the number of mutations in melanoma skin cancer; the most serious form of skin cancer. Many non-red haired people carry these common variants and the study shows that everyone needs to be careful about sun exposure.

Red-headed people make up between one and two percent of the world’s population but about 6 per cent of the UK population. They have two copies of a variant of the MC1R gene which affects the type of melanin pigment they produce, leading to red hair, freckles, pale skin and a strong tendency to burn in the sun.

“It has been known for a while that a person with red hair has an increased likelihood of developing skin cancer, but this is the first time that the gene has been proven to be associated with skin cancers with more mutations.”

“Unexpectedly, we also showed that people with only a single copy of the gene variant still have a much higher number of tumour mutations than the rest of the population. This is one of the first examples of a common genetic profile having a large impact on a cancer genome and could help better identify people at higher risk of developing skin cancer.”

Dr David Adams Joint lead researcher at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The researchers analysed publically available data-sets of tumour DNA sequences collected from more than 400 people. They found an average of 42 per cent more sun-associated mutations in tumours from people carrying the gene variant.

“This is the first study to look at how the inherited MC1R gene affects the number of spontaneous mutations in skin cancers and has significant implications for understanding how skin cancers form. It has only been possible due to the large-scale data available. The tumours were sequenced in the USA, from patients all over the world and the data was made freely accessible to all researchers. This study illustrates how important international collaboration and free public access to data-sets is to research.”

Professor Tim Bishop Joint lead author and Director of the Leeds Institute of Cancer and Pathology at the University of Leeds

“This important research explains why red-haired people have to be so careful about covering up in strong sun. It also underlines that it isn’t just people with red hair who need to protect themselves from too much sun. People who tend to burn rather than tan, or who have fair skin, hair or eyes, or who have freckles or moles are also at higher risk.”

“For all of us the best way to protect skin when the sun is strong is to spend time in the shade between 11am and 3pm, and to cover up with a t-shirt, hat and sunglasses. And sunscreen helps protect the parts you can’t cover; use one with at least SPF15 and 4 or more stars, put on plenty and reapply regularly.”

Dr Julie Sharp Head of health and patient information at Cancer Research UK

More information

Participating Centres

- Experimental Cancer Genetics, The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, Cambridgeshire CB10 1SA, UK.

- Laboratorio Internacional de Investigacio´n sobre el Genoma Humano, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Campus Juriquilla, Boulevard Juriquilla 3001, Santiago de Queretaro 76230, Mexico

- The Cancer Genome Project, The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, Cambridgeshire CB10 1SA, UK

- Department of Pharmacology, Boston University School of Medicine. Boston, Massachusetts 02128, USA.

- MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge Institute of Public Health, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Cambridge CB2 0SR, UK.

- Division of Population Health Sciences, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, 123 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland.

- Department of Pathology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut 06519, USA.

- Department of Dermatology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut 06519, USA.

- Program in Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut 06519, USA.

- Section of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Leeds Institute of Cancer and Pathology, University of Leeds, Leeds, LS9 7TF, UK.

Funding

This work was funded by Cancer Research UK and the Wellcome Trust.

Publications:

Selected websites

International Laboratory for Human Genome Research, National Autonomous University of Mexico

The International Laboratory for Human Genome Research is a new initiative of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, one of the largest universities in the world. Its academic strength lies in its international collaborations and young faculty, who work in genome dynamics and evolution, regulatory genomics, population genetics, cancer biology and the genomics of brain development and function.

Leeds University

The University of Leeds is one of the largest higher education institutions in the UK, with more than 31,000 students from 147 different countries, and a member of the Russell Group research-intensive universities. We are a top 10 university for research and impact power in the UK, according to the 2014 Research Excellence Framework, and positioned as one of the top 100 best universities in the world in the 2015 QS World University Rankings.

Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is one of the world’s leading genome centres. Through its ability to conduct research at scale, it is able to engage in bold and long-term exploratory projects that are designed to influence and empower medical science globally. Institute research findings, generated through its own research programmes and through its leading role in international consortia, are being used to develop new diagnostics and treatments for human disease.

Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.