Protein essential to the spread of malaria uncovered

The protein, AP2-G, is necessary for switching on genes that control the development of precursor malaria cells to the male and female forms of the parasite – the only stage that is infectious to mosquitos. This solves a long-standing mystery in malaria biology and has important implications for malaria-control strategies.

Sexual reproduction is a vulnerable stage of the parasite’s complicated life cycle. This stage can only occur in the gut of the mosquito after it has sucked the precursor parasite cells out of a person’s blood.

“Current drugs treat patients by killing the sexless form of the parasite in their blood – this is the detrimental stage of the malaria lifecycle that causes illness. However, it is now widely accepted that to eliminate malaria from an entire region, it will be equally important to kill the sexual forms that transmit the disease.”

Dr Oliver Billker Co-lead author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

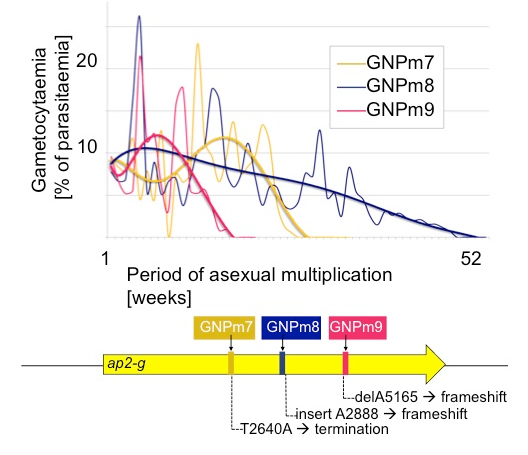

The ability of the malaria parasite to produce precursor cells to the sexual male and female form of the parasite can be lost through continuous culturing in the lab or continuous blood transfer. The team generated three parasite cell lines that have lost this ability in the lab.

They sequenced the genomes of these parasites and found that common mutations to the ap2-g gene in all three cell lines appeared to underlie the inability of the parasite to progress to the sexual-stage of its lifecycle.

To confirm these observations, the team silenced the ap2-g gene in the parasite and found that the manipulated parasites lost the ability to generate sexual stage parasites.

“Our studies discovered that if we switch off AP2-G in a parasite cell, then that cell cannot grow into a sexual-stage parasite. This means that the parasite cannot move from the infected person back into the mosquito to continue the cycle, making transmission of that parasite from one human to another impossible.”

Dr Andy Waters Co-lead author from the University of Glasgow

Furthermore, when this mutated gene was then repaired through ‘gene therapy’, the parasites regained the ability to progress to the sexual stage. Combined with other experiments, their results showed that sexual-stage malaria parasites are produced only when the AP2-G protein is in good working order.

“Having discovered the master switch, we can now begin to unravel how exactly sexual parasite stages form and get ready to transmit malaria. This will reveal new ways in which drugs and vaccines can be developed to stop transmission.”

Dr Katarzyna Modrzynska Author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

This research paper will be published in Nature along with a second paper that separately details the role of AP2-G as a master switch in controlling sexual stage commitment of malaria parasites.

“Exciting opportunities now lie ahead for finding an effective way to break the chain of malaria transmission by preventing the malaria parasite from completing its full life cycle. This sexual-stage bottleneck is an enticing target for interventions to prevent this comparatively small, yet critical number of sexual parasites from forming.”

Dr Manuel Llinás From Penn State University, who is lead author of a second study also describing the discovery of AP2-G

These studies open the way to the development of screens for effective drugs that could disable commitment to sexual development and prevent transmission.

More information

Funding

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust, Evimalar, Medical Research Council, NIH, Centre for Quantitative Biology and the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation.

Participating Centres

- Wellcome Trust Centre for Molecular Parasitology, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK

- Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, Cambridge, UK

- Department of Molecular Biology and Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, USA

- Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and Center for Infectious Disease Dynamics, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA

Publications:

Selected websites

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is one of the world’s leading genome centres. Through its ability to conduct research at scale, it is able to engage in bold and long-term exploratory projects that are designed to influence and empower medical science globally. Institute research findings, generated through its own research programmes and through its leading role in international consortia, are being used to develop new diagnostics and treatments for human disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.