Dental decay: the evolution of oral diversity

Researchers have traced the evolutionary changes in the human diet by comparing bacteria preserved in the tooth plaque of early European settlers. This is the first detailed genetic record of the evolution of human microbiota.

Two dietary shifts have greatly altered the composition of our oral microbiota; the first from hunter-gatherer to farmer and the second, the industrial revolution. The team have identified that these shifts have greatly diminished the diversity of oral bacteria and may be a contributing factor to modern disease.

Bacteria can become crystallized in dental calculus or plaque that forms on teeth, preserving their DNA for thousands of years. This archaeological dental calculus has the potential to trace human population structure and movement, and trace the spread of disease in ancient cultures.

“We knew these dietary shifts occurred but this is the first time we can see how the bacteria that live in the mouth have responded to these shifts. Our study is a proof of concept, it is possible to take a sample that is thousands of years old and sequence the bacteria that are present to better understand cultural and dietary shifts in prehistoric humans.”

Dr Alan Walker Co-author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

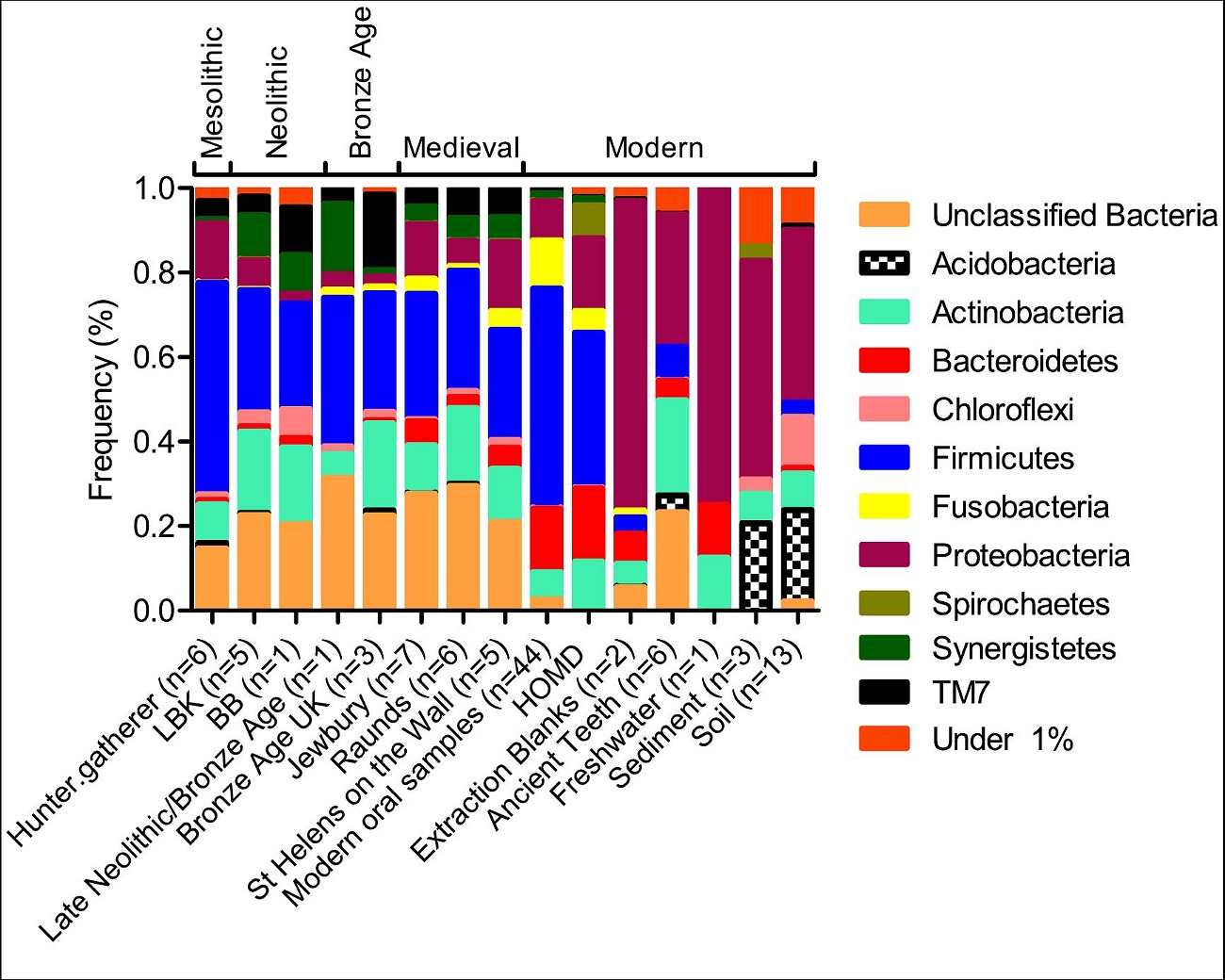

The team collected 34 samples of dental plaque from people from the last hunter-gatherers in Poland, the earliest farmers from Central Europe, as well as late Neolithic, Bronze Age and medieval populations.

Using DNA sequencing, they found that the composition of oral bacteria underwent a distinct shift with the introduction of farming, with earlier hunter-gatherers displaying fewer disease-causing bacteria. This was likely caused by an increase in starch and carbohydrates into people’s diets.

The team found that there was a great increase in Streptococcus mutans, the bacterium most responsible for tooth decay, in modern samples compared to pre-industrial revolution samples. This change is linked to the shift in food processing technology and production of flour and sugar during the industrial revolution.

“It is clear from our study that the diversity of modern human’s oral bacteria is much reduced compared with our prehistoric hunter-gatherer and early farming ancestors who existed over 7,500 years ago. Over the past few hundred years, our mouths have clearly become a substantially less diverse ecosystem, reducing our resilience to invasions by disease-causing bacteria.”

Professor Keith Dobney Co-author from the University of Aberdeen

This study provides the first views about the timing and nature of changes in human oral bacterial composition and diversity over the past 7,500 years. This method has the potential to look in new ways directly at the effects of nutritional and cultural transitions through time.

“Our research has opened the door to exploring the history of humans’ changing diets and the relationship with bacteria. We have shown that microbiota sequencing is not restricted to modern samples; we can now take samples that are thousands of years old and successfully sequence them.

“Sequencing and comparing the oral microbiota of different populations, over the ages, from across the world will tell us how different diets have affected human health.”

Dr Julian Parkhill Co-author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

More information

Funding

Supported by the Australian Research Council, Wellcome Trust and the Sir Mark Mitchell Foundation.

Participating Centres

- Australian Centre for Ancient DNA, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences and Environment Institute, The University of Adelaide, South Australia 5005, Australia Institute of Dental Research, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

- Department of Archaeology, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB24 3UF, Scotland, United Kingdom

- School of Dentistry, The University of Adelaide, South Australia 5005, Australia

- The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, Cambridgeshire, CB10 1SA, United Kingdom

- The Environment Institute and School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of Adelaide, South Australia 5005, Australia

- South Australian Research and Development Institute, PO Box 120, Henley Beach SA 5022, Australia

- Department of Bioarchaeology, Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw Poland

- Institute for Anthropology, Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz, Mainz, Germany

Publications:

Selected websites

University of Aberdeen

The University of Aberdeen is today at the forefront of teaching, learning and discovery, as it has been for 500 years. As the ‘global university of the north’, it has consistently sent pioneers and ideas outward to every part of the world. It is an ambitious, research-driven university with a global outlook, committed to excellence in everything it does.

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is one of the world’s leading genome centres. Through its ability to conduct research at scale, it is able to engage in bold and long-term exploratory projects that are designed to influence and empower medical science globally. Institute research findings, generated through its own research programmes and through its leading role in international consortia, are being used to develop new diagnostics and treatments for human disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.