New strain of MRSA discovered

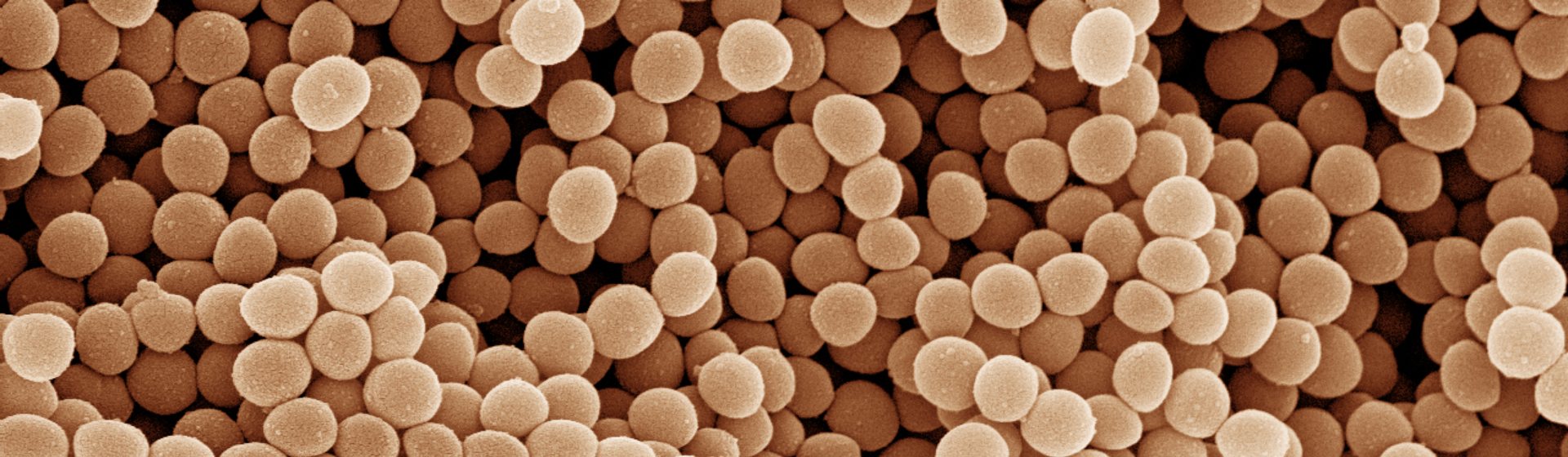

Scientists have identified a new strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) which occurs both in human and dairy cow populations.

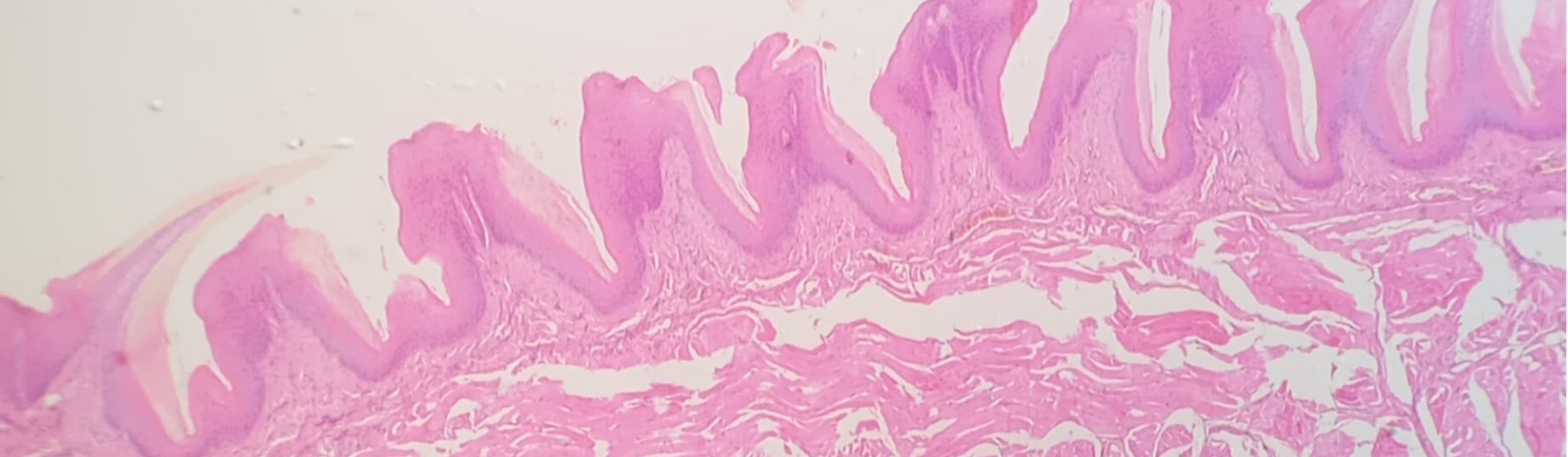

The study, led by Dr Mark Holmes at the University of Cambridge, identified the new strain in milk from dairy cows while researching mastitis (a bacterial infection which occurs in the cows’ udders).

The new strain’s genetic makeup differs greatly from previous strains, which means that the ‘gold standard’ molecular tests currently used to identify MRSA – a polymerase chain reaction technique (PCR) and slide agglutination testing – do not detect this new strain. The research findings are published today in the journal The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

“To find the same new strain in both humans and cows is certainly worrying. However, pasteurization of milk will prevent any risk of infection via the food chain. Workers on dairy farms may be at higher risk of carrying MRSA, but we do not yet know if this translates into a higher risk of infection. In the wider UK community, less than 1 per cent of as many individuals carry MRSA – typically in their noses – without becoming ill.”

Dr Laura García-Álvarez First author of the paper, who discovered the new strain while a PhD student at the University of Cambridge’s Veterinary School

The scientists discovered the antibiotic resistant strain while researching S. aureus, a bacterium known to cause bovine mastitis. Despite the strain being able to grow in the presence of antibiotics, when they attempted to use the standard molecular tests available – which work by identifying the presence of the gene responsible for methicillin resistance (the mecA gene) – the tests came back negative for MRSA.

When Dr Matt Holden and a research team at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute sequenced the entire genome (decoding all of the genes in the bacteria’s DNA) they realised that the new strain possessed unconventional DNA for MRSA. They found that the new strain does have a mecA gene but with only 60 per cent similarity to the original mecA gene. Unfortunately, this results in molecular tests (which identify MRSA by the presence of the mecA gene) giving a false negative for this strain of MRSA.

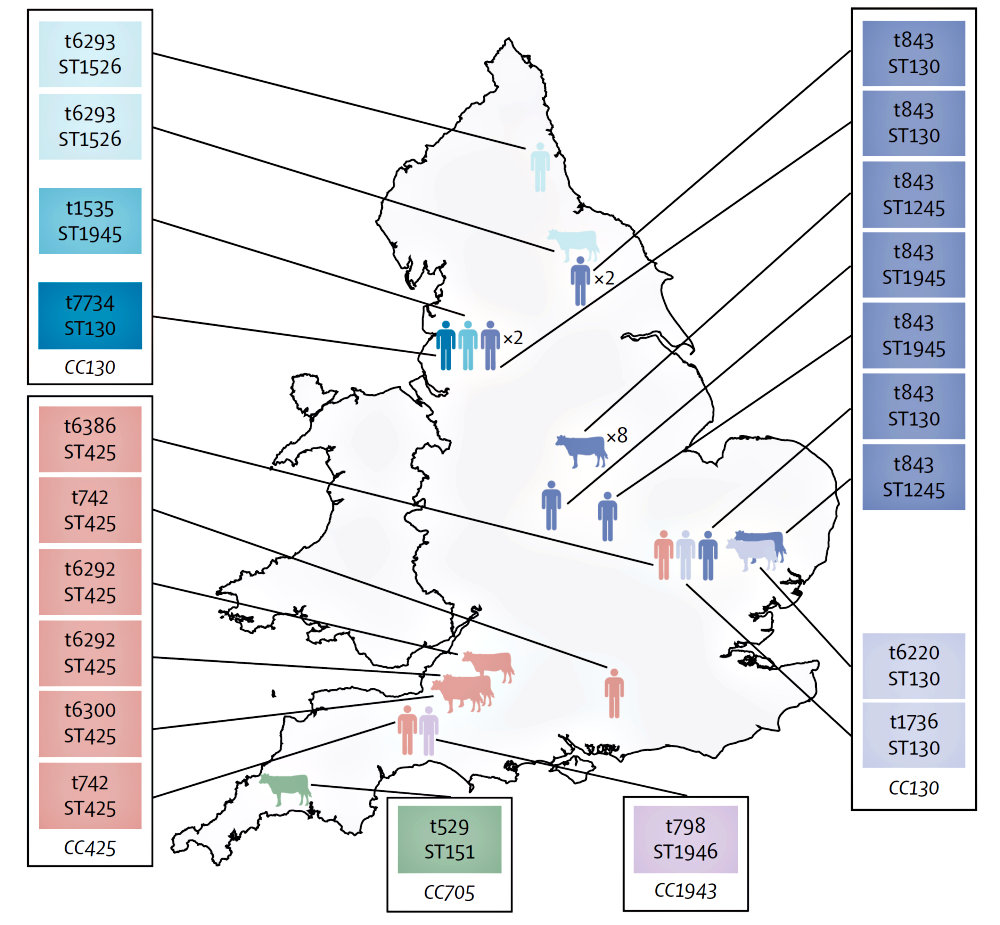

Subsequent research revealed that the new strain was also present in humans. During the study, the new strain was found in samples from Scotland, England and Denmark (some from screening tests and others from people with MRSA disease). It has since been identified in Ireland and Germany. Additionally, by testing archived S. aureus samples, the researchers have also identified a recent upward trend in the prevalence of the antibiotic resistant bacteria.

“The majority of MRSA testing in British hospitals is performed by seeing if the bacteria will grow in the presence of antibiotics, typically oxacillin and cefoxitin, rather than methicillin – which is now no longer manufactured. This type of testing detects both the new MRSA and conventional MRSA.

“However, it is important that any of the MRSA testing that is based on detection of the mecA gene – i.e. PCR based testing, or slide agglutination testing – be upgraded to ensure that the tests detect the new mecA gene found in the new MRSA. We have already been working with public health colleagues in the UK and Denmark to ensure that testing in these countries now detects the new MRSA.”

Dr Mark Holmes University of Cambridge

The new research also raises questions about whether cows could be a reservoir for the new strains of MRSA.

“Although there is circumstantial evidence that dairy cows are providing a reservoir of infection, it is still not known for certain if cows are infecting people, or people are infecting cows. This is one of the many things we will be looking into next.

“Although our research suggests that the new MRSA accounts for a small proportion of MRSA – probably less than 100 isolations per year in the UK, it does appear that the numbers are rising. The next step will be to explore how prevalent the new strain actually is and to track where it is coming from. If we are ever going to address the problem with MRSA, we need to determine its origins.”

Dr Mark Holmes University of Cambridge

Scientists at the Health Protection Agency (HPA) co-authored this paper, providing the analysis of the human samples of the new strain.

“There are numerous strains of MRSA circulating in the UK and the rest of Europe. Even though this new strain is not picked up by the current molecular tests, the tests do still remain effective for the detection of over 99 per cent of MRSAs. This new strain can be picked up by another type of test, which has shown to be effective in trials in the UK and elsewhere in Europe.

“This is a very interesting find and the HPA is currently involved in further research to screen a wider population of MRSA samples to ascertain how prevalent it is. It’s important to remember MRSA is still treatable with a range of antibiotics and the risk of becoming infected with this new strain is very low.”

Dr Angela Kearns Head of the Health Protection Agency Staphylococcus Reference Laboratory

With funding from the Medical Research Council, the researchers will next be undertaking prevalence surveys in people and in dairy cattle in the UK to determine how much new MRSA is present in these populations. They will also be performing an epidemiological study on farms to identify any factors that may be associated with infection by the new MRSA, to look for further new MRSA strains, and to explore the potential risks of the new strain to farm workers.

More information

Funding

Funding was provided by Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and the Higher Education Funding Council for England, the Isaac Newton Trust (Trinity College, University of Cambridge, UK), the Wellcome Trust, the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

Participating Centres

- Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge UK

- Health Protection Agency, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge UK

- The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge UK

- Veterinary Laboratories Agency, Harlescott, Shrewsbury UK

- Microbiology Services Division, Health Protection Agency, London UK

- Department of Antimicrobial Surveillance and Research, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark

- Scottish MRSA Reference Laboratory, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Stobhill Hospital, Glasgow UK

- Department of Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge UK

Publications:

Selected websites

The Health Protection Agency

The Health Protection Agency is an independent UK organisation that was set up by the government in 2003 to protect the public from threats to their health from infectious diseases and environmental hazards. It does this by providing advice and information to the general public, to health professionals such as doctors and nurses, and to national and local government. In 2012 the HPA will become part of Public Health England.

Medical Research Council

For almost 100 years the Medical Research Council has improved the health of people in the UK and around the world by supporting the highest quality science. The MRC invests in world-class scientists. It has produced 29 Nobel Prize winners and sustains a flourishing environment for internationally recognised research. The MRC focuses on making an impact and provides the financial muscle and scientific expertise behind medical breakthroughs, including one of the first antibiotics penicillin, the structure of DNA and the lethal link between smoking and cancer. Today MRC funded scientists tackle research into the major health challenges of the 21st century.

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, which receives the majority of its funding from the Wellcome Trust, was founded in 1992. The Institute is responsible for the completion of the sequence of approximately one-third of the human genome as well as genomes of model organisms and more than 90 pathogen genomes. In October 2006, new funding was awarded by the Wellcome Trust to exploit the wealth of genome data now available to answer important questions about health and disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.