One mutation every day

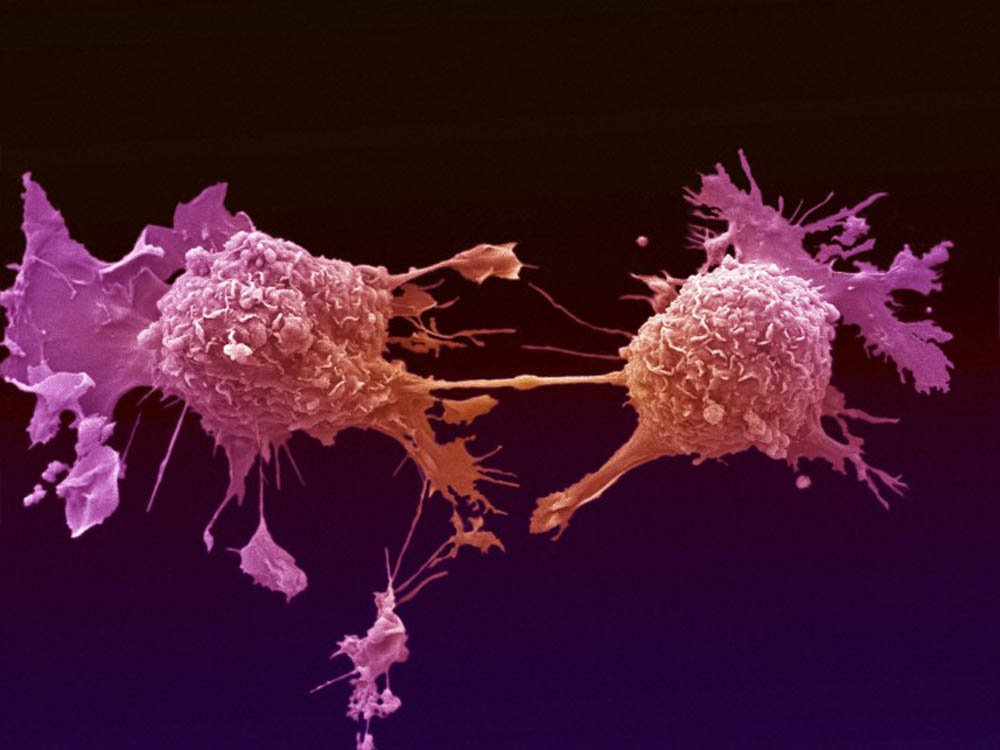

Research published in Nature shows that the genome of a lung cancer patient has more than 20,000 mutations: this total implies that a typical smoker would acquire one mutation for every 15 cigarettes smoked. The cancer genome is ravaged by mutations, many of which are repaired as the genome tries to defend itself.

In many cases, that battle is lost and some of the many thousands of mutations hit key genes and lead to cancer.

In the study, the researchers compared the genomes in normal blood cells and tumour cells from a patient with small cell lung cancer (SCLC). They sequenced the genome a total of 60 times over to develop a comprehensive catalogue of all known types of DNA mutation.

“For the first time, we have a comprehensive map of all mutations in a cancer cell. The profile of mutations we observed is exactly that expected from tobacco, suggesting that the majority of the 23,000 we found are caused by the cocktail of chemicals found in cigarettes. On the basis of average estimates, we can say that one mutation is fixed in the genome for every 15 cigarettes smoked.”

Dr Peter Campbell Senior author on the work, from the Cancer Genome Project at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The mutations range from single-letter changes in the code to deletions or rearrangements of hundreds of thousand of letters. Most are ‘passenger’ mutations, previously defined by the team as mutations that do not influence the development of the cancer, but are a consequence of the highly mutagenic environment in many cancer cells.

“Cancers occur when control of cell behaviour is lost – cells grow how, when and where they shouldn’t. Mutations in DNA caused by, for example, cigarette smoke are passed on to every subsequent generation of daughter cells, a permanent record of the damage done. Like an archaeologist, we can begin to reconstruct the history of the cancer clone – revealing a record of past exposure and accumulated damage in the genome.”

Dr Andy Futreal from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The study was so comprehensive that the team could see signatures of an undiscovered system of DNA repair Reducing the mutations in highly active genes, suggesting the genome seeks to preserve these regions above many others.

However, as previous studies suggested, there was not one mutation that stood out as ‘the lung cancer gene’. One gene – CHD7 – was found to be mutated in several SCLC samples. This gene is part of an emerging pattern that cancers often contain mutations in genes that are generalists in regulating genetic activity alongside more specific changes.

This work and the companion study on malignant melanoma using massively parallel sequencing portend an era in which the forces of mutagens shaping our genome can be described and the consequences of these processes can be decoded.

It is clear that rates of lung cancer fall to around normal some 15 years after quitting smoking: the suspicion is that lung cells containing mutations are replaced by new cells derived from lung stem cells that are clear of mutation.

“This is a difficult disease to diagnose and treat, but fortunately we do know how people can minimize their risk of lung cancer. Even current smokers substantially reduce their risk by giving up now – the more time passes off tobacco, the more the risk decreases.”

Professor Mike Stratton, Sanger Institute

Notes and statistics

Globally, lung cancer claims more than one in six cancer deaths each year. Of the two major types, small cell lung cancer is found in 15 per cent of cases, but has much the worse prognosis, with only one in 20 patients surviving for five years.

Cancer of the respiratory tract (lung, trachea, bronchus) is the most common cause of death from cancer in Europe and the USA.

WHO global infobase

More information

Funding

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust. Support for individual researchers was from the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund, Human Frontiers Science Program and the National Cancer Institute.

Publications:

Selected websites

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, which receives the majority of its funding from the Wellcome Trust, was founded in 1992. The Institute is responsible for the completion of the sequence of approximately one-third of the human genome as well as genomes of model organisms and more than 90 pathogen genomes. In October 2006, new funding was awarded by the Wellcome Trust to exploit the wealth of genome data now available to answer important questions about health and disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.