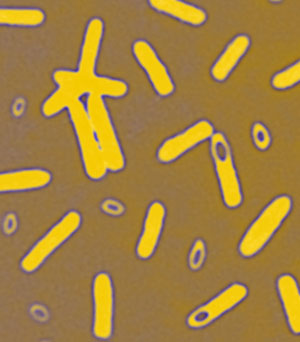

Botulism bug has few genome wrinkles

The genome of the organism that produces the world’s most lethal toxin is revealed today. This toxin is the one real weapon in the genome of Clostridium botulinum and less than 2 kg – the weight of two bags of sugar – is enough to kill every person on the planet. Very small amounts of the same toxin are used in medical treatments, one of which is known as Botox®.

The genome of the organism that produces the world’s most lethal toxin is revealed today. This toxin is the one real weapon in the genome of Clostridium botulinum and less than 2 kg – the weight of two bags of sugar – is enough to kill every person on the planet. Very small amounts of the same toxin are used in medical treatments, one of which is known as Botox®.

The genome sequence shows that C. botulinum doesn’t have subtle tools to evade our human defences or tricky methods of acquiring resistance to antibiotics. It lives either as a dormant spore or as a scavenger of decaying animal materials in the soil, and doesn’t interact with human or other large animal hosts for prolonged periods of time.

Occasionally it gets into a living animal, via contaminated food or open wounds, leading to infant botulism or wound botulism, both of which are serious human infections. The host can be quickly overpowered and, in some cases, killed by the toxin, and C. botulinum has a new food source.

“Although in the same group as Clostridium difficile – the Cdiff superbug – C. botulinum has a genome that is remarkable because it is so stable. Unlike Cdiff, in which more than 10 per cent of genes have been acquired from other bacteria, there is almost no footprint of these in C. botulinum.”

Dr Mohammed Sebaihia Lead author on the paper from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

There are several types of C. botulinum: although described as variants of a single species, they are really very different organisms linked simply because they have the deadly toxin. For each type, there is also a near-identical but harmless relative that lacks the toxin. C. sporogenes is the non-malignant, near twin of the organism sequenced.

“It is astonishing that 43 per cent of the predicted genes in the C. botulinum genome are absent from the other five sequenced clostridia, and only 16 per cent of the C. botulinum genes are common to all five. Our findings emphasise just how different clostridia are from each other.”

Professor Mike Peck From the Institute of Food Research

C. botulinum toxin stops nerves from working – the basis of its use in medicine to control tremors and in cosmetic treatments. For the prey of its opportunistic attacks, death is swift. Perhaps the most important tool it has to act out its stealth attacks is its ability to hibernate when times are hard by forming dormant spores.

More than 110 of its set of almost 3700 genes are used to control spore formation and germination when opportunity arises.

“C. botulinum shows us one extreme of the ways that bacteria can make the most of animal hosts. Some organisms use subtle approaches, elegantly choreographing their interaction with us and our defences.

“C. botulinum takes the opposite approach. It lies in wait and, if it gets the opportunity, it hits its host with a microbial sledgehammer. It then eats the remains and lays low until the next host comes along.”

Dr Julian Parkhill of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The genome sequence is peppered with genes that produce enzymes to digest proteins and other animal material in the soil. Also found Uniquely in this species, is a range of genes that allow it to attack the many insect and other small creatures that live in the soil. The ‘chitinases’ produced by these genes can degrade the casing of insects and small crustaceans.

It is not only animals that can feel the wrath of C. botulinum.

“The soil can be a harsh environment and food can be scarce. To see off the competition, C. botulinum comes with its own ‘antibiotic’ – a chemical called boticin that kills competing bacteria.”

Dr Sebaihia

Genome sequences can tell us a lot about the biology of the organism, but research into clostridia has been hampered by the lack of a good genetic system. Professor Nigel Minton, Professor of Applied Molecular Microbiology at the University of Nottingham, has developed new methods to knock out genes in clostridia.

“Even after decades of research, only a handful of mutants had been made in clostridia, and none in C. botulinum. We have developed a highly efficient system, the ClosTron, with which we have, in a few months, knocked out over 30 genes in four different clostridial species, including eight in C. botulinum. The availability of this tool should revolutionise functional genomic studies in clostridia.”

Professor Nigel Minton,Professor of Applied Molecular Microbiology at the University of Nottingham

This remarkable, stable genome demonstrates the wide range of strategies used by bacteria to enhance their chances of survival. For the Clostridia, these range from the approach used by C. difficile – long-term interaction with hosts, which involves evading the immune system and countering antibiotics – to the single-minded opportunistic approach of C. botulinum.

More information

Funding

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust, a competitive strategic grant from the BBSRC and a CRTI1-IRTC operating grant.

Participating Centres

- Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge, CB10 1SA, UK

- Institute of Food Research, Norwich Research Park, Colney, Norwich, NR4 7UA, UK

- Centre for Biomolecular Sciences, Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, School of Molecular Medical Sciences, University of Nottingham, University Park, Nottingham NG7 2RD, UK

- School of Life Sciences, Heriot-Watt University, Riccarton, Edinburgh EH14 4AS, UK

- Bureau of Microbial Hazards, Health Canada, Tunney’s Pasture, Ottawa, ON, K1A 26 0L2, Canada

Publications:

Selected websites

About the IFR

The mission of the Institute of Food Research (http://www.ifr.ac.uk/) is to undertake international quality scientific research relevant to food and human health and to work in partnership with others to provide underpinning science for consumers, policy makers , the food industry and academia. It is a company limited by guarantee, with charitable status, grant aided by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (http://www.bbsrc.ac.uk/).

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, which receives the majority of its funding from the Wellcome Trust, was founded in 1992. The Institute is responsible for the completion of the sequence of approximately one-third of the human genome as well as genomes of model organisms and more than 90 pathogen genomes. In October 2006, new funding was awarded by the Wellcome Trust to exploit the wealth of genome data now available to answer important questions about health and disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is the largest charity in the UK. It funds innovative biomedical research, in the UK and internationally, spending around £500 million each year to support the brightest scientists with the best ideas. The Wellcome Trust supports public debate about biomedical research and its impact on health and wellbeing.