Malaria's severity reset by mosquito

The route of infection modifies the malaria parasite’s gene activity levels and regulates the parasite’s spread in the blood by controlling the mouse’s immune response. This study begins to understand how protective immunity to malaria occurs, an important step for the development of effective vaccines.

Researchers have known that the severity of symptoms of malaria increases when the malaria parasite is transferred repeatedly through blood samples in mice rather than by a mosquito, but up until now they have not known why.

“Understanding how malaria becomes more or less virulent is central to understanding how to manage and treat the disease. We studied a rodent malaria species, that exhibits many of the same responses as seen in a human malaria infection. Our understanding of how the parasite interacts with the immune system is fundamentally changed by this study.”

Dr Matt Berriman A senior author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

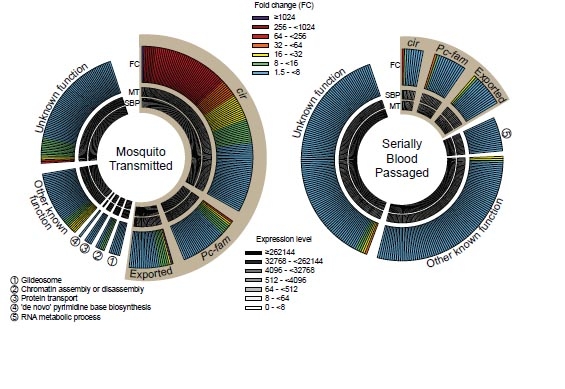

To explore the effect that the route of transmission had, the team examined the levels of gene activity in the malaria parasite during its life cycle in mice.

They found that P. chabaudi chabaudi ‘resets’ its genetic activity when it is transmitted between the mosquito and mouse, making it less virulent. However, transferring the parasite through multiple blood transfers between mice in the laboratory loses this resetting. Because there is no reset the malaria parasite multiples much more quickly in mice after blood transfers, and causes an increase in disease severity.

The team uncovered a direct association between a specific gene family in the malaria parasite, known as cir genes, and the control of severity of the disease symptoms in mice. It appears that malaria parasite genes control the immune response of mice to the disease.

“Our research is helping to better understand vaccine targets. RNA sequencing allowed us to identify a set of Plasmodium genes that control the immune response and the degree of severity of the disease in mice. We anticipate that we will be able to transfer the findings from our study in mice to human malaria studies, the next phase of our research.”

Dr Adam Reid Author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The team expect that the cir gene family plays a role in activating the immune system and controls the level of parasite in the blood to keep malaria from harming the host. This is the largest gene family in malaria parasites, including the deadly human parasite, P. falciparum.

“These results place the mosquito at the centre of our efforts to pick apart the processes behind protective immunity to malaria. Malaria is both preventable and curable but still has a huge burden on those who are vulnerable to severe forms of the infection, mostly young children. Understanding protective immunity in the body would be an important first step towards developing an effective vaccine.”

Dr Jean Langhorne Leader of the study, based at the Medical Research Council National Institute for Medical Research

More information

Funding

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust.

Participating Centres

- Division of Parasitology, MRC National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR), Mill Hill, London, UK

- Parasite Genomics, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, Cambridge, UK

Publications:

Selected websites

Medical Research Council

Over the past century, the Medical Research Council has been at the forefront of scientific discovery to improve human health. Founded in 1913 to tackle tuberculosis, the MRC now invests taxpayers’ money in some of the best medical research in the world across every area of health. Twenty-nine MRC-funded researchers have won Nobel prizes in a wide range of disciplines, and MRC scientists have been behind such diverse discoveries as vitamins, the structure of DNA and the link between smoking and cancer, as well as achievements such as pioneering the use of randomised controlled trials, the invention of MRI scanning, and the development of a group of antibodies used in the making of some of the most successful drugs ever developed.

Today, MRC-funded scientists tackle some of the greatest health problems facing humanity in the 21st century, from the rising tide of chronic diseases associated with ageing to the threats posed by rapidly mutating micro-organisms.

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is one of the world’s leading genome centres. Through its ability to conduct research at scale, it is able to engage in bold and long-term exploratory projects that are designed to influence and empower medical science globally. Institute research findings, generated through its own research programmes and through its leading role in international consortia, are being used to develop new diagnostics and treatments for human disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.