How ionising radiation damages DNA and causes cancer

Published in Nature Communications today, the results will also help to explain how radiation can cause cancer.

Ionising radiation, such as gamma rays, X-rays and radioactive particles can cause cancer by damaging DNA. However, how this happens, or how many tumours are caused by radiation damage has not been known.

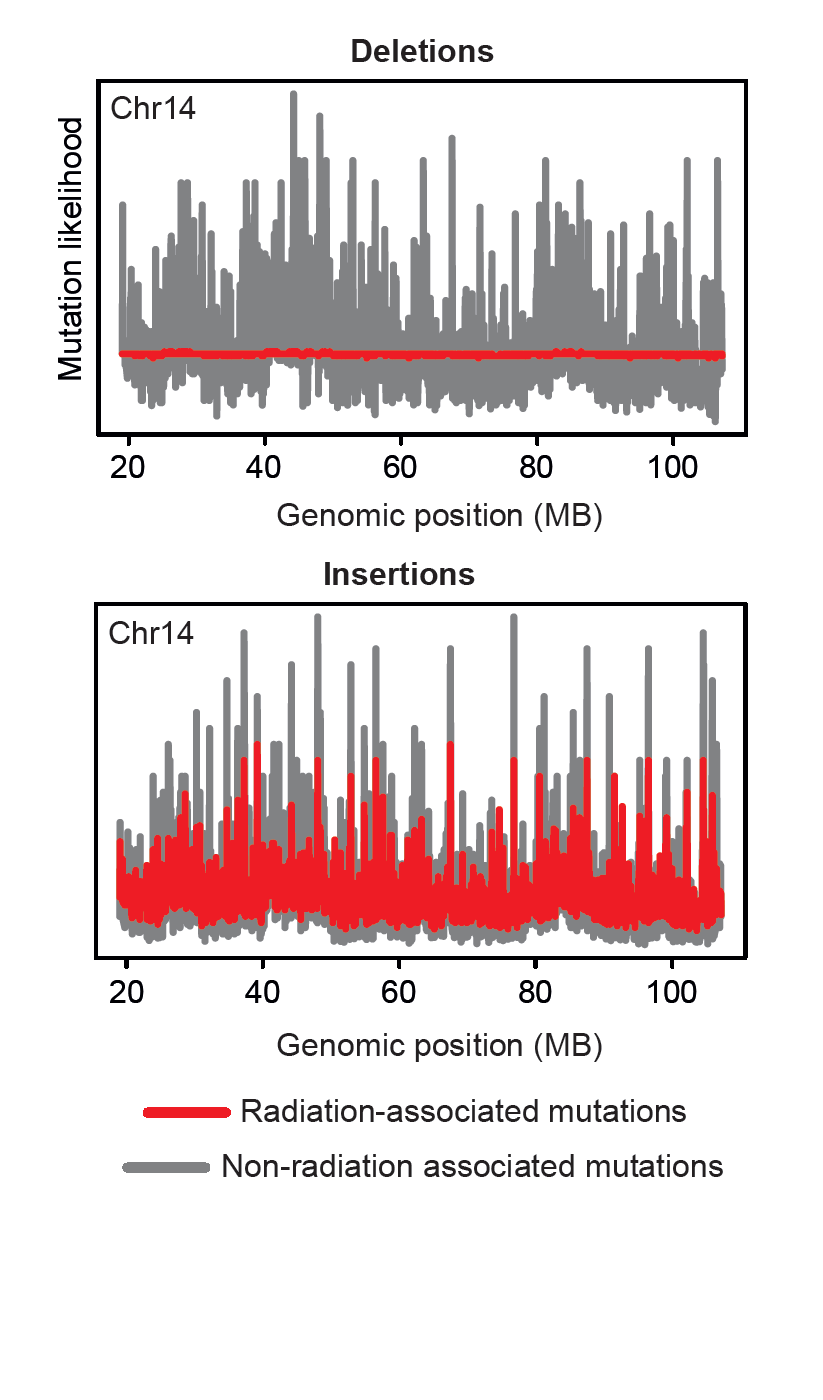

Previous work on cancer had revealed that DNA damage often leaves a molecular fingerprint, known as a mutational signature, on the genome of a cancer cell. The researchers looked for mutational signatures in 12 patients with secondary radiation-associated tumours, comparing these with 319 that had not been exposed to radiation.

“To find out how radiation could cause cancer, we studied the genomes of cancers caused by radiation in comparison to tumours that arose spontaneously. By comparing the DNA sequences we found two mutational signatures for radiation damage that were independent of cancer type. We then checked the findings with prostate cancers that had or had not been exposed to radiation, and found the same two signatures again. These mutational signatures help us explain how high-energy radiation damages DNA.”

Dr Peter Campbell leader of the study and Head of the Cancer Genome Project at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

One mutational signature is a deletion where small numbers of DNA bases are cut out. The second is called a balanced inversion Where the DNA is cut in two places, the middle piece spins round, and is joined back again in the opposite orientation. Balanced inversions don’t happen naturally in the body, but high-energy radiation could provide enough DNA breaks at the same time to make this possible.

“Ionising radiation probably causes all types of mutational damage, but here we can see two specific types of damage and get a sense of what is happening to the DNA. Showers of radiation chop up the genome causing lots of damage simultaneously. This seems to overwhelm the DNA repair mechanism in the cell, leading to the DNA damage we see.”

Dr Sam Behjati, clinician researcher at the Sanger Institute and the Department of Paediatrics, University of Cambridge

“This is the first time that scientists have been able to define the damage caused to DNA by ionising radiation. These mutational signatures could be a diagnosis tool for both individual cases, and for groups of cancers, and could help us find out which cancers are caused by radiation. Once we have better understanding of this, we can study whether they should be treated the same or differently to other cancers.”

Professor Adrienne Flanagan A collaborating cancer researcher from University College London and Royal National Orthopaedic hospital

More information

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Wellcome Trust (grant reference 077012/Z/05/Z), Skeletal Cancer Action Trust, Rosetrees Trust UK, Bone Cancer Research Trust and the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit in Chemical and Radiation Hazards and Threats at Newcastle University in partnership with Public Health England, National Institute for Health Research, UCLH Biomedical Research Centre, and the CRUK UCL Experimental Cancer Centre.

Publications:

Selected websites

University College London (UCL)

UCL was founded in 1826. We were the first English university established after Oxford and Cambridge, the first to open up university education to those previously excluded from it, and the first to provide systematic teaching of law, architecture and medicine. We are among the world’s top universities, as reflected by performance in a range of international rankings and tables. UCL currently has over 35,000 students from 150 countries and over 11,000 staff. Our annual income is more than £1 billion. www.ucl.ac.uk | Follow us on Twitter @uclnews | Watch our YouTube channel YouTube.com/UCLTV

Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital

The RNOH is the largest specialist orthopaedic hospital in the UK and a recognised world leader in the field of orthopaedics and neuro-musculoskeletal medicine. It treats more than 120,000 patients a year for conditions ranging from acute spinal injuries to sarcoma. As well as being a leading centre for surgery and rehabilitation, RNOH also has an international reputation and track record for innovative translational research, working in close partnerships with University College London (UCL) and the Royal Free Hospital.

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is one of the world’s leading genome centres. Through its ability to conduct research at scale, it is able to engage in bold and long-term exploratory projects that are designed to influence and empower medical science globally. Institute research findings, generated through its own research programmes and through its leading role in international consortia, are being used to develop new diagnostics and treatments for human disease.

Wellcome

Wellcome exists to improve health for everyone by helping great ideas to thrive. We’re a global charitable foundation, both politically and financially independent. We support scientists and researchers, take on big problems, fuel imaginations and spark debate.