Early-stage embryos with abnormalities can still develop into healthy babies

Abnormal cells in the early embryo are not necessarily a sign that a baby will be born with a birth defect such as Down’s syndrome, suggests new research from the University of Cambridge, the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and the University of Leuven, Belgium. In a study published today (29 March) in the journal Nature Communications, scientists show that abnormal cells are eliminated and replaced by healthy cells, repairing – and in many cases completely fixing – the embryo.

Researchers at the Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience at Cambridge report a mouse model of aneuploidy, where some cells in the embryo contain an abnormal number of chromosomes. Normally, each cell in the human embryo should contain 23 pairs of chromosomes (22 pairs of chromosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes), but some can carry multiple copies of chromosomes, which can lead to developmental disorders. For example, children born with three copies of chromosome 21 will develop Down’s syndrome.

Pregnant mothers – particular older mothers, whose offspring are at greatest risk of developing such disorders – are offered tests to predict the likelihood of genetic abnormalities. Between the 11th and 14th weeks of pregnancy, mothers may be offered chorionic villus sampling (CVS), a test that involves removing and analysing cells from the placenta. A later test, known as amniocentesis, involves analysing cells shed by the foetus into the surrounding amniotic fluid – this test is more accurate, but is usually carried out during weeks 15-20 of the pregnancy, when the foetus is further developed.

Professor Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, the study’s senior author, was inspired to carry out the research following her own experience when pregnant with her second child. At the time, a CVS test found that as many as a quarter of the cells in the placenta that joined her and her developing baby were abnormal: could the developing baby also have abnormal cells? When Professor Zernicka-Goetz spoke to geneticists about the potential implications, she found that very little was understood about the fate of embryos containing abnormal cells and about the fate of these abnormal cells within the developing embryos.

Fortunately for Professor Zernicka-Goetz, her son, Simon, was born healthy.

“I am one of the growing number of women having children over the age of 40 – I was pregnant with my second child when I was 44. I know how lucky I was and how happy I felt when Simon was born healthy.

“Many expectant mothers have to make a difficult choice about their pregnancy based on a test whose results we don’t fully understand. What does it mean if a quarter of the cells from the placenta carry a genetic abnormality – how likely is it that the child will have cells with this abnormality, too? This is the question we wanted to answer. Given that the average age at which women have their children is rising, this is a question that will become increasingly important.”

Professor Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz A senior study author from the Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience, University of Cambridge

“In fact, abnormal cells with numerical and/or structural anomalies of chromosomes have been observed in as many as 80-90 per cent of human early-stage embryos following in vitro fertilization and CSV tests may expose some degree of these abnormalities.”

Professor Thierry Voet from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute UK, and the University of Leuven, Belgium, another senior author of the paper

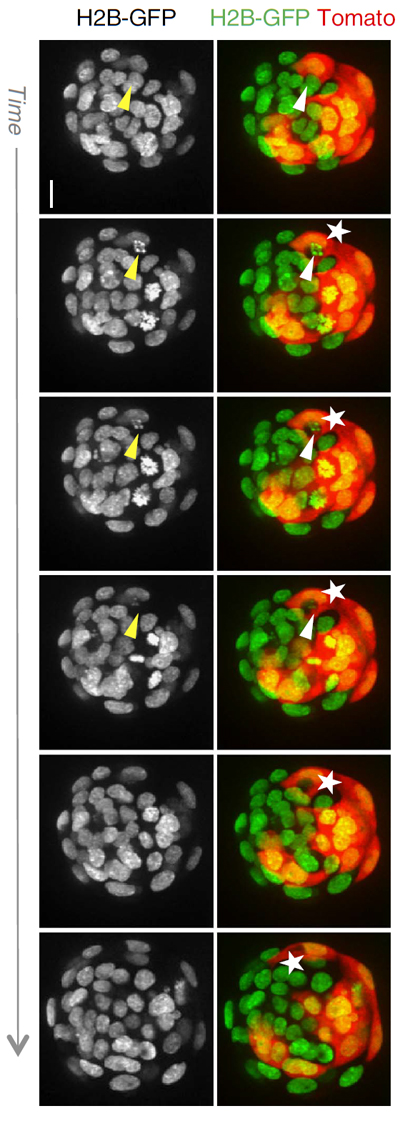

In research funded by the Wellcome Trust, Professor Zernicka-Goetz and colleagues developed a mouse model of aneuploidy by mixing 8-cell stage mouse embryos in which the cells were normal with embryos in which the cells were abnormal. Abnormal mouse embryos are relatively unusual, so the team used a molecule known as reversine to induce aneuploidy.

In embryos where the mix of normal and abnormal cells was half and half, the researchers observed that the abnormal cells within the embryo were killed off by ‘apoptosis’, or programmed cell death, even when placental cells retained abnormalities. This allowed the normal cells to take over, resulting in an embryo where all the cells were healthy. When the mix of cells was three abnormal cells to one normal cell, some of abnormal cells continued to survive, but the ratio of normal cells increased.

“The embryo has an amazing ability to correct itself. We found that even when half of the cells in the early-stage embryo are abnormal, the embryo can fully repair itself. This means that even when early indications suggest a child might have a birth defect because there are some, but importantly not all abnormal cells in its embryonic body, this isn’t necessarily the case.”

Professor Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz

The researchers will now try to determine the exact proportion of healthy cells needed to completely repair an embryo and the mechanism by which the abnormal cells are eliminated.

More information

Publications:

Selected websites

About the University of Cambridge

The mission of the University of Cambridge is to contribute to society through the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence. To date, 90 affiliates of the University have won the Nobel Prize. Founded in 1209, the University comprises 31 autonomous Colleges, which admit undergraduates and provide small-group tuition, and 150 departments, faculties and institutions. Cambridge is a global university. Its 19,000 student body includes 3,700 international students from 120 countries. Cambridge researchers collaborate with colleagues worldwide, and the University has established larger-scale partnerships in Asia, Africa and America. The University sits at the heart of one of the world’s largest technology clusters. The ‘Cambridge Phenomenon’ has created 1,500 hi-tech companies, 14 of them valued at over US$1 billion and two at over US$10 billion. Cambridge promotes the interface between academia and business, and has a global reputation for innovation.

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is one of the world’s leading genome centres. Through its ability to conduct research at scale, it is able to engage in bold and long-term exploratory projects that are designed to influence and empower medical science globally. Institute research findings, generated through its own research programmes and through its leading role in international consortia, are being used to develop new diagnostics and treatments for human disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.