Study set to shape medical genetics in Africa

Researchers from the African Genome Variation Project (AGVP) have published the first attempt to comprehensively characterise genetic diversity across Sub-Saharan Africa. The study of the world’s most genetically diverse region will provide an invaluable resource for medical researchers and provides insights into population movements over thousands of years of African history. These findings appear in the journal Nature.

“Although many studies have focused on studying genetic risk factors for disease in European populations, this is an understudied area in Africa. Infectious and non-infectious diseases are highly prevalent in Africa and the risk factors for these diseases may be very different from those in European populations.

“Given the evolutionary history of many African populations, we expect them to be genetically more diverse than Europeans and other populations. However we know little about the nature and extent of this diversity and we need to understand this to identify genetic risk factors for disease.”

Dr Deepti Gurdasani Lead author on the study and a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

Dr Manjinder Sandhu and colleagues collected genetic data from more than 1800 people – including 320 whole genome sequences from seven populations – to create a detailed characterisation of 18 ethnolinguistic groups in Sub-Saharan Africa. Genetic samples were collected through partnerships with doctors and researchers in Ethiopia, the Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Uganda.

The AGVP investigators, who are funded by the Wellcome Trust, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health and the UK Medical Research Council, found 30 million genetic variants in the seven sequenced populations, a fourth of which have not previously been identified in any population group. The authors show that in spite of this genetic diversity, it is possible to design new methods and tools to help understand this genetic variation and identify genetic risk factors for disease in Africa.

“The primary aim of the AGVP is to facilitate medical genetic research in Africa. We envisage that data from this project will provide a global resource for researchers, as well as facilitate genetic work in Africa, including those participating in the recently established pan-African Human Heredity and Health in Africa (H3Africa) genomic initiative.”

Dr Charles Rotimi Senior author from the Centre for Research on Genomics and Global Health, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA.

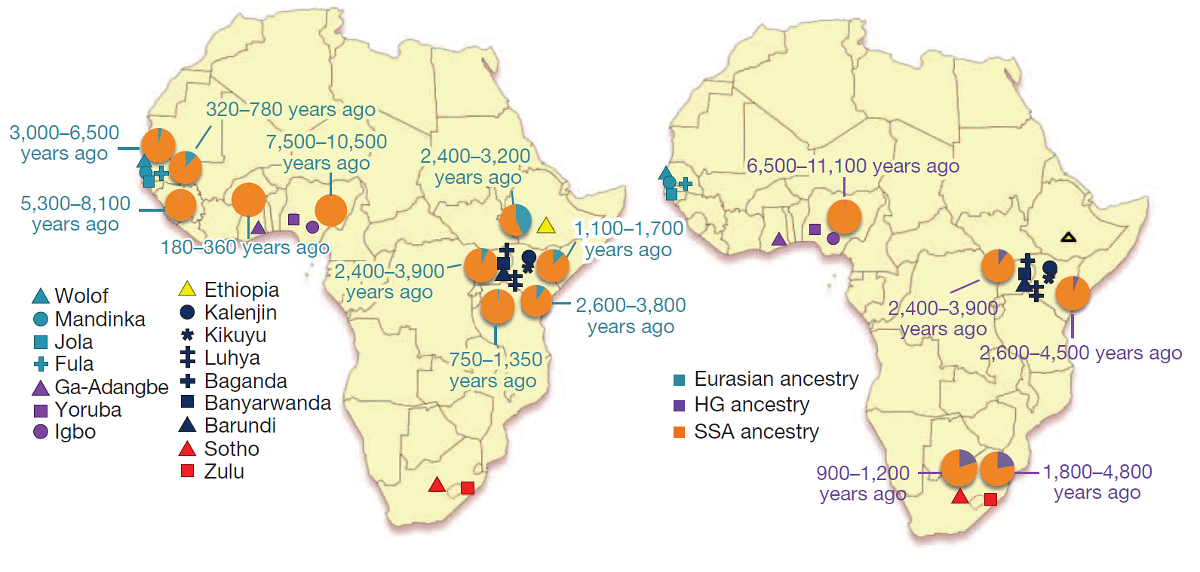

The authors also found evidence of extensive European or Middle Eastern genetic ancestry among several populations across Africa. These date back to 9,000 years ago in West Africa, supporting the hypothesis that Europeans may have migrated back to Africa during this period. Several of the populations studied are descended from the Bantu, a population of agriculturists and pastoralists thought to have expanded across large parts of Africa around 5,000 years ago.

The authors found that several hunter-gatherer lines joined the Bantu populations at different points in time in different parts of the continent. This provides important insights into hunter-gatherer populations that may have existed in Africa prior to the Bantu expansion. It also means that future genetic research may require a better understanding of this hunter-gatherer ancestry.

“The AGVP has provided interesting clues about ancient populations in Africa that pre-dated the Bantu expansion. To better understand the genetic landscape of ancient Africa we will need to study modern genetic sequences from previously under-studied African populations, along with ancient DNA from archaeological sources.”

Dr Manjinder Sandhu Lead senior author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, UK and the Department of Medicine, University of Cambridge

The study also provides interesting clues about possible genetic loci associated with increased susceptibility to high blood pressure and various infectious diseases, including malaria, Lassa fever and trypanosomiasis, all highly prevalent in some regions of Africa. These genetic variants seem to occur with different frequencies in disease endemic and non-endemic regions, suggesting that this may have occurred in response to the different environments these populations have been exposed to over time.

“The AGVP has substantially expanded on our understanding of African genome variation. It provides the first practical framework for genetic research in Africa and will be an invaluable resource for researchers across the world. In collaboration with research groups across Africa, we hope to extend this resource with large-scale sequencing studies in more of these diverse populations.”

Dr Manjinder Sandhu

More information

Publications:

Selected websites

African Genome Variation Project

The African Genome Variation Project aims to collect essential information about the structure of African genomes to provide a basic framework for genetic disease studies in Africa.

University of Cambridge

The mission of the University of Cambridge is to contribute to society through the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence. To date, 90 affiliates of the University have won the Nobel Prize. Founded in 1209, the University comprises 31 autonomous Colleges, which admit undergraduates and provide small-group tuition, and 150 departments, faculties and institutions. Cambridge is a global university. Its 19,000 student body includes 3,700 international students from 120 countries. Cambridge researchers collaborate with colleagues worldwide, and the University has established larger-scale partnerships in Asia, Africa and America. The University sits at the heart of one of the world’s largest technology clusters. The ‘Cambridge Phenomenon’ has created 1,500 hi-tech companies, 12 of them valued at over US$1 billion and two at over US$10 billion. Cambridge promotes the interface between academia and business, and has a global reputation for innovation.

Medical Research Council

The Medical Research Council has been at the forefront of scientific discovery to improve human health. Founded in 1913 to tackle tuberculosis, the MRC now invests taxpayers’ money in some of the best medical research in the world across every area of health. Thirty MRC-funded researchers have won Nobel prizes in a wide range of disciplines, and MRC scientists have been behind such diverse discoveries as vitamins, the structure of DNA and the link between smoking and cancer, as well as achievements such as pioneering the use of randomised controlled trials, the invention of MRI scanning, and the development of a group of antibodies used in the making of some of the most successful drugs ever developed. Today, MRC-funded scientists tackle some of the greatest health problems facing humanity in the 21st century, from the rising tide of chronic diseases associated with ageing to the threats posed by rapidly mutating micro-organisms.

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is one of the world’s leading genome centres. Through its ability to conduct research at scale, it is able to engage in bold and long-term exploratory projects that are designed to influence and empower medical science globally. Institute research findings, generated through its own research programmes and through its leading role in international consortia, are being used to develop new diagnostics and treatments for human disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.