A Switch for Lung Cancer

One in five people in the developed world will die of the diseases we call cancer. What they die of is not one disease, but a bewildering array of cancers, each of which behaves differently, grows differently and – crucially – responds to treatment differently.

One of the goals of the Cancer Genome Project at The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is to bring order to our understanding of the differences between cancers. By cataloguing the changes within the genomes of cancer cells and identifying the mutant genes responsible for the development of the disease, we will better be able to choose the best treatments for each patient and search for new treatments.

As reported in Nature on Thursday 30 September 2004, the team and their colleagues have identified a gene (ERBB2) involved in 4 per cent of non-small-cell lung cancers (NSCLCs), a type of lung cancer. Most significantly, they propose that an existing drug might work in individuals that carry mutations in the ERBB2 gene.

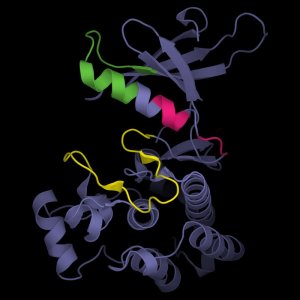

“ERBB2 is one of a series of biological ‘switches’ in our cells that plays a vital role in controlling whether cells survive and proliferate. When the ERBB2 protein is switched on, it talks to other molecules in the cell to initiate a cascade of changes that alter how cells grow.”

“Some mutations in the ERBB2 protein make it appear to the other molecules as if it were switched on all the time. The consequence is uncontrolled cell division – cancer.”

“What we found is that the ERBB2 activating mutation occurs in 4 per cent of lung cancers (non-small-cell lung cancers, NSCLC) and in 10 per cent of a particular type called adenocarcinoma.”

Dr Andy Futreal, Co-Leader of the Cancer Genome Project

Perhaps 40 per cent of all lung cancers are adenocarcinomas and the number appears to be increasing. A role for ERBB2 has been suggested in other cancers, including breast cancer, and a drug called trastuzumab (Herceptin), which dampens the activity of ERBB2, has been developed to help treat these.

The Cancer Genome Project results are the first time a mutation within the ERBB2 gene has been found in tumour cases. The Project team suggest that trastuzumab and other anti-ERBB2 agents should be tried in patients who carry mutations of the type they have discovered.

“We have an existing drug that works against the overactive ERBB2 protein. And can now identify patients with NSCLC who have mutations in this gene. Our understanding from other studies suggests that these patients may benefit from treatment with anti-ERBB2 agents.”

“With this strategy of searching for the root causes of gene problems we have an opportunity to make progress in the treatment of other cancers. I have to stress, however, we are still a long, long way from cures.”

“Picking apart the biology that underlies cell behaviour in cancer will help us define what has gone wrong and how it has gone wrong. In many cases we will need to seek new treatments but in some – such as this – we will be able to see which patients might be helped by carefully chosen existing medicines.”

Dr Andy Futreal Sanger Institute

The role of ERBB2 in cancer has been suspected for more than 15 years. It is only with strategies such as those used by the Cancer Genome Project that it is becoming possible to identify cancer patients who may have a mutations in particular target genes.

“Understanding cancer genetics is beginning to transform our treatment of these diseases. When we understand specific aberrations in cancer cells, we can begin to find ways to target them and to prevent them from dividing and spreading.”

“Using genomic sequences we can begin to develop new treatments, based on the subtle differences in the diseases we call cancer. We may also find that treatments developed for one type may also have considerable benefit in other types of cancer. That is one of the most exciting aspects of this report.”

“We are still some way from unravelling the relevant genomic sequences in all forms of cancer and further still from finding treatments. But we have turned a corner and the bringing together of DNA sequence, patient samples and basic research provides renewed hope that we know where we should go.”

“While advances such as these hold out considerable hope for lung cancer patients, we must remember that the greatest impact in this disease relates to persuading people to stop smoking.”

Professor Stan Kaye Cancer Research UK Professor of Medical Oncology at the Institute of Cancer Research and Royal Marsden Hospital

Cells that contain mutations leading to overactivity of proteins like ERBB2 appear to become ‘addicted’ to the mutant protein: its overactivity becomes important for continued survival of the cell. One consequence is that drugs that inhibit the overactive protein have a greater effect on mutant cells than on cells without the mutation.

More information

About lung cancer

Lung cancer is the second most common form of cancer in the UK (the most common is breast cancer). About 90% of lung cancers are due to smoking or passive smoking. There are more than 38,000 new cases of lung cancer in the UK each year. Perhaps 40% of lung cancers are adenocarcinomas, characterized by cube-shaped tumour cells.

About new cancer therapies

Control of cell division and cell death is mediated by cascades of protein switches, many of which are enzymes of a type called protein kinases. The protein kinases are ‘switched on’ in turn to process the signal telling the cell to divide, or to move, or to die. When one component of the cascade is not switched off, the cascade will continue to run and the cell will not return to its normal state. If a kinase involved in cell death or cell division is mutated and appears to be switched on, the cell will not die as intended or will continue to divide when it should not.

On the basis if this, several new treatments have been developed designed to inhibit these overactive proteins. Some are small-molecule inhibitors, others are antibodies: both recognize the protein and prevent its action.

The first to be developed for clinical use was Gleevec (Imatinib), which inhibits several protein kinases – in particular, three called ABL, PDGF-R and C-KIT. Gleevec is effective in treating chronic myelogenous leukaemia (CML) and a number of other tumours in which the ABL gene is mutated. It also is effective in some patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumours – but only if those patients have a mutation in the C-KIT gene. Other patients with apparently the same cancer but no mutation in C-KIT appear to gain no benefit from treatment with Gleevec.

Herceptin – now called trastuzumab – is an antibody that recognizes and inhibits the ERBB2 protein. It is a treatment of choice in breast cancer patients with a mutation of the ERBB2 gene. More than 125,000 breast cancer patients with ERBB2 gene amplification have been treated with Herceptin since marketing approval in the US 1998.

The Cancer Genome Project

is using the human genome sequence and high-throughput mutation detection techniques to identify somatically acquired sequence variants/mutations and hence identify genes critical in the development of human cancers. This initiative will ultimately provide the paradigm for the detection of germline mutations in non-neoplastic human genetic diseases through genome-wide mutation detection approaches.

Publications:

Selected websites

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, which receives the majority of its funding from the Wellcome Trust, was founded in 1992. The Institute is responsible for the completion of the sequence of approximately one-third of the human genome as well as genomes of model organisms and more than 90 pathogen genomes. In October 2006, new funding was awarded by the Wellcome Trust to exploit the wealth of genome data now available to answer important questions about health and disease.

The Wellcome Trust and Its Founder

The Wellcome Trust is the most diverse biomedical research charity in the world, spending about £450 million every year both in the UK and internationally to support and promote research that will improve the health of humans and animals. The Trust was established under the will of Sir Henry Wellcome, and is funded from a private endowment, which is managed with long-term stability and growth in mind.